Unit 6: Morality Beyond Universal Rules & Principles

Photo: Dean Holland / NBC.

Like the Utilitarians, Aristotle believes that happiness is the chief good and end of human life. Aristotle’s conception of happiness, however, is not about pleasure. Instead it describes an activity of the soul exhibiting virtue. This leads into an extended discussion about the virtuous character traits that a person ought to have in order to live a happy life and be a good person. This module introduces this idea of Virtue Ethics along with how a person might actually acquire such virtue in their life.

To that end, we have 5 learning outcomes. By the end of this module, you will be able to…

- Explain the meaning of and relationships between eudaimonia, aretē, and psuche as they are used by Aristotle;

- Describe Aristotle’s division of the human soul and the associated virtues of each of those aspects;

- Apply Aristotle’s definition of moral virtue to break down the meaning of each of the particular virtues that he catalogues;

- Reflect on the moral virtues that you would wish to cultivate for yourself; and

- Summarize Aristotle’s account for how we may acquire the moral virtues.

Read & Annotate This:

|

Virtue Ethics: Aristotle &

|

Context

There is a long tradition in ethics that places great importance on the “kind of person one is”. We not only want those around us to “tell the truth”, but also want them to be honest people. Persons with such dispositions, or with such “character”, can then be trusted to act responsibly and deal with others fairly. Aristotle’s concept of moral virtue emphasizes this aspect of ethics.

Aristotle is not easy to read, so we will primarily focus on Jonathan Wolff’s (2018) analysis of Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics. Here we see how Aristotle connects the idea of a happy life to a morally good life of virtue.

As Wolff notes, Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics argues that true happiness come from acting in a way that exercises our uniquely human abilities. This may sound familiar from Module 17 and John Stuart Mill’s understanding of happiness. Indeed, Mill read Aristotle and so he might have been trying to make Aristotle’s ideas more Utilitarian. As the reading suggests, though, Aristotle himself was no Utilitarian. For instance, Aristotle rejects the idea that happiness is pleasure, nor does he talk about aggregating happiness and maximizing the greater good.

To the contrary, Aristotle suggests that to truly understand happiness, we must first understand what makes us human. To understand that, Aristotle says, we must do an analysis of our soul. (Aristotle pre-dates Christianity by a few centuries, so as you will soon see, his conception of the human soul is quite different from what you might expect.) In that analysis, Aristotle identifies the different parts of the human soul and the types of virtue associated with each of them. Exercising all these virtues is then supposed to constitute human happiness. Wolff primarily considers the moral virtues that Aristotle associates with our character, which Aristotle’s (2009b) catalogues in some detail.

If you would like to dig in a little more deeply, I have included (in the optional “Curious for More?” section below) Aristotle’s (2009a) analysis of happiness, the human soul, and moral virtue. If you followed the Wolff reading and my videos, I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised at how much you can draw out from this classic work of philosophy.

Finally, I have also included (again, in the optional “Curious for More?” section below) a video on Virtue Ethics from Hank Green that he did for CrashCourse (2016).

Reading Questions

As you read, keep these questions in mind:

- How does Jonathan Wolff characterize Aristotle’s understanding of the good life and eudaimonia (human flourishing, the human good)? How does Aristotle go about determining the nature of human flourishing? What is the “human good” according to Aristotle? What seems to be the relationship between that human good and pleasure?

- Wolff very briefly mentions (on page 204) the different parts of the soul that Aristotle considers. What are these parts? Which do we share with other animals and which are unique to humans?

- Wolff notes that one important topic in Virtue Ethics is moral development, that is, how we acquire moral virtue. According to Aristotle, how do we acquire it?

- What is Aristotle’s account of the “golden mean”? What sort of relationship does this establish between virtue and vice? Is this supposed to be a mathematical average? Is this golden mean the same for everybody?

-

Aristotle (2009b) talks about different moral virtues. For each virtue, he provides the following:

Can you identify these three things for each of the virtues Aristotle names?A. The name of the virtue, B. The substrate(s) or continuum(s) of emotion and/or activity connected to that virtue, and C. The nature of the vices associated with that virtue.

Although I strongly suggest that you write out brief answers to these questions, you do not have to turn in written responses. You do, however, need to be prepared to answer questions like these on module quizzes and the unit exams.

References

Aristotle. (2009a). Nicomachean ethics. (W. D. Ross, Trans., L. Brown, Ed.). Oxford University Press. (Original work from ca. 350 B.C.E.)

Aristotle. (2009b). [Particular moral virtues]. In W. D. Ross (Trans.) & L. Brown, (Ed.), Nicomachean ethics (pp. 32–34). Oxford University Press. (Original work from from ca. 350 B.C.E.)

CrashCourse. (2016, December 5). Aristotle & Virtue Theory: Crash Course Philosophy #38 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrvtOWEXDIQ

Wolff, J. (2018). Virtue ethics: Aristotle. In An introduction to moral philosophy (pp. 200–218). W. W. Norton & Company.

Watch This:

|

Video 1

|

Video 2

|

|

Video 3

|

Video 4

|

|

Video 5

|

Video 6

|

|

Video 7

|

Video 8

|

Do This:

|

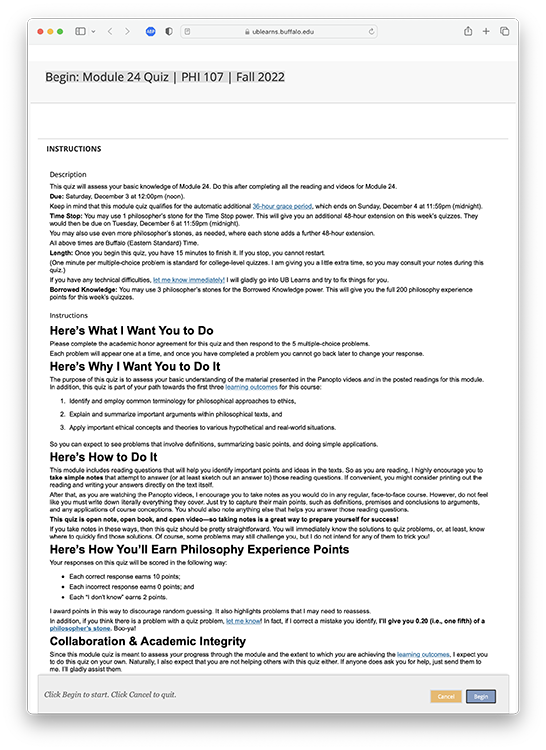

Module 24 Quiz

Due: December 3 |

Tweets for the Week

Due: December 3 |

Curious for More? (Optional)

|

Nicomachean Ethics

|

Turns out that your favorite (substitute) teacher knows a thing or two about Aristotle & Virtue Ethics!