Reviving curiosity

It is theoretically possible to travel abroad and, hearing English widely spoken, conclude that language study in English-speaking countries is not a practical necessity. Yet this is not in fact the consensus at the JFK arrivals terminal. Travellers who venture off the tour bus even briefly yearn to communicate with the people who live in the countries whose monuments and natural wonders they've come to admire. It is widely recognized that travel abroad is one of the best ways to motivate language study, hence the importance of even short excursions for high school students. What struck me during this summer's trip was the way in which travel reawakens all curiosity, not just linguistic.

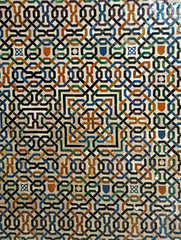

We began our travels in mid-May with a brief stop in Spain so that our visit of Morocco could properly start with a tour of Alhambra.

From Granada we took a bus south to Almeria and from there a ferry to Melilla, a Spanish possession on Morocco's eastern Mediterrannean coast. We walked across the border into Morocco amid jostling crowds of people of every age and condition ferrying contraband by means of the most improbable conveyances: a refrigerator on a hand cart pushed by an old man along the rubble, shrink-wrapped 48-pack bundles of paper towels balanced on either side of a creeking bicycle, soft drinks by the dozens being ported on the heads of women with babies slung over their backs. Then there were other products we could only guess at, as these were transported swiftly along clandestine parallel passages through rotting buildings. Access to these passages was allowed by the stern and watchful customs inspectors who saw to it that proper respect was accorded to them, if not to the government they represent.

Two taxi rides later and we were in Ouijda (pronounced WIDGE-da), where we were received like royalty by our friends and former UB students Larbi Touaf and Soumia Boutkhil. Larbi and Soumia had returned to Morocco to take up full-time tenure-line positions shortly after the birth of their son Nassef in summer 2001. Their cordial hospitality allowed us to glimpse family life here, to grasp something of the distinct features of Moroccan society, and to taste Moroccan cuisine as prepared by a family. It was also a very great pleasure to see them again as friends, especially now that they are parents.

Our favorite item in Moroccan cuisine has been harira (particularly in Ouijda!), a soup which has a meat and tomato base and is flavored with cilantro. We have enjoyed a spread like peanut butter made with argan oil, meat-filled pastries called pastillas, a griddle-cooked bread called msemmin, the well-known couscous, far better here than in France, as are the Moroccan pastries. We've tried a variety of tajines, and I'm still trying to figure out what constitutes its basic recipe. The word may mean something as generic as casserole, and seems to refer to an earthenware dish: a plate on a short pedestal, and a conical lid with a small rounded disk at the top which serves as a handle. We have seen even omelets served, piping hot, in this dish, and they are everywhere for sale as souvenirs. Fresh fruit juices are everywhere available. Coffee is available but not apparently a very imporant drink; mint tea is the national beverage.

Larbi and Soumia arranged for me to give a presentation on the Litgloss web project and to meet with campus officials -- the dean and associate dean of the faculty of arts and humanities -- to discuss a university partnership with UB. There are many potential areas for joint research and teaching. Both Buffalo and Ouijda are border towns -- Ouijda is a twenty-minute car ride from the Algerian border. All of the northern Mediterrannean region of Morocco is indeed something of a frontier. From a hill overlooking Melilla (known here as Melilia), Larbi showed me the massive separation wall surrounding this Spanish town through which we had arrived. "Wow -- so this is the wall separating Melilia from the rest of Morocco," I said, to which he replied, "No -- this is the wall separating Europe from Africa." In Ouijda, on the campus of Mohamed I University itself, there is a camp of sub-Saharan Africans hoping for passage to or through Morocco, and in the hillside forests overlooking Melilia (and apparently also near Ceuta/Septa), there are sub-Saharan Africans who have been in hiding for generations. Thus (among many to be mentioned later) border / migration studies is an area for research collaboration between our two universities, and could include work on human rights (what is the legal status of people living in these semi-permanent transitional encampments?) and the political use of refugees -- Morocco is negotiating free trade status with the EU, and the vigilance it exercises over its borders is a card to be played. When free trade is established in 2012, the contraband traffic across the border with Melilia will adapt or disappear.

The same cannot be said for the black market in gasoline: since Algeria is an oil-producing country, gas is significantly cheaper there than on the other side of the frontier. So for miles and miles along the highway, runners in stolen stripped-down cars ferry gas in 40-litre bidons piled into their trunk and back seat. The prevalence of this contraband gas makes it impossible for regular gas stations to stay in business -- in some towns there simply are none -- and consequently the entire population is dependent on gas trafficking for personal use, mass transit, and agricultural equipment and transport.

The highlight of our stay in northeastern Morocco was an excursion to the Cap des Trois Fourches, a small peninsula which juts out into the Mediterranean near Nador.

The excursion was organized by two members of the science faculty at the University of Mohamed I and had the organizational backing of the local French cultural services. The tour leaders -- a geologist and a biologist -- seemed to have trained in France, and they desribed the mission of their excursions as being the promotion of "la culture scientifique," meaning general knowledge and understanding of science among non-scientists. There were about 20 people on the outing -- high school teachers, a banker, a journalist, a former pilot and his family, some young women in a group, and then L&S&N and their Buffalo guests.

The excursion was brilliantly designed to arouse curiosity about the extraordinary local geological formations at precisely the moment when the desired explanation was available -- JIT Gen Ed, we might say. The same was true for the botany lessons -- the specialization of the biologist was phytopharmaceuticals.

On this wonderfully choreographed excursion I again felt what I have often observed: that in my case, at least, it is not merely linguistic ignorance that travel makes me regret, but ALL my lacunae. Off the coast of Rabat, a few days later, I wandered onto the most extraordinary reef, where in pockets formed millions of years ago -- or so I think -- there now live colonies of sea urchins. How I regretted the incurie of my youth, when I might have learned what I needed to complete my admiration of this enchanting scene.

And history! and economics! I reach to recover what I ever knew of the Almoravids, but alas, there is nothing to remember, for during that lesson, as during so many others, I was not curious to know what the teacher had been assigned to require.

I remember the sidelong exchange of regards narquois among high school classmates when the program of the day was to learn how to read the indicateur du chemin de fer, than which no more ridiculous and futile learning could be imagined by the contemptuous class. Surely proper pedagogy begins by creating or reviving the relevant curiosity. Tired Gen Ed instructors across the disciplines could do worse than to send their students abroad in their first semester to rescue them from a learned indifference.

It is reported that infants are able to discriminate between thousands of sounds, and that the acquisition of language requires us to lose interest in the myriad phonetic nuances we might have cared about in order to notice only those which are phonemic, that is to say, functional. I wonder if this narrowing is assumed to be necessary in all areas of learning... and if the deadening of our curiosity isn't a terrible waste?

We began our travels in mid-May with a brief stop in Spain so that our visit of Morocco could properly start with a tour of Alhambra.

From Granada we took a bus south to Almeria and from there a ferry to Melilla, a Spanish possession on Morocco's eastern Mediterrannean coast. We walked across the border into Morocco amid jostling crowds of people of every age and condition ferrying contraband by means of the most improbable conveyances: a refrigerator on a hand cart pushed by an old man along the rubble, shrink-wrapped 48-pack bundles of paper towels balanced on either side of a creeking bicycle, soft drinks by the dozens being ported on the heads of women with babies slung over their backs. Then there were other products we could only guess at, as these were transported swiftly along clandestine parallel passages through rotting buildings. Access to these passages was allowed by the stern and watchful customs inspectors who saw to it that proper respect was accorded to them, if not to the government they represent.

Two taxi rides later and we were in Ouijda (pronounced WIDGE-da), where we were received like royalty by our friends and former UB students Larbi Touaf and Soumia Boutkhil. Larbi and Soumia had returned to Morocco to take up full-time tenure-line positions shortly after the birth of their son Nassef in summer 2001. Their cordial hospitality allowed us to glimpse family life here, to grasp something of the distinct features of Moroccan society, and to taste Moroccan cuisine as prepared by a family. It was also a very great pleasure to see them again as friends, especially now that they are parents.

Our favorite item in Moroccan cuisine has been harira (particularly in Ouijda!), a soup which has a meat and tomato base and is flavored with cilantro. We have enjoyed a spread like peanut butter made with argan oil, meat-filled pastries called pastillas, a griddle-cooked bread called msemmin, the well-known couscous, far better here than in France, as are the Moroccan pastries. We've tried a variety of tajines, and I'm still trying to figure out what constitutes its basic recipe. The word may mean something as generic as casserole, and seems to refer to an earthenware dish: a plate on a short pedestal, and a conical lid with a small rounded disk at the top which serves as a handle. We have seen even omelets served, piping hot, in this dish, and they are everywhere for sale as souvenirs. Fresh fruit juices are everywhere available. Coffee is available but not apparently a very imporant drink; mint tea is the national beverage.

Larbi and Soumia arranged for me to give a presentation on the Litgloss web project and to meet with campus officials -- the dean and associate dean of the faculty of arts and humanities -- to discuss a university partnership with UB. There are many potential areas for joint research and teaching. Both Buffalo and Ouijda are border towns -- Ouijda is a twenty-minute car ride from the Algerian border. All of the northern Mediterrannean region of Morocco is indeed something of a frontier. From a hill overlooking Melilla (known here as Melilia), Larbi showed me the massive separation wall surrounding this Spanish town through which we had arrived. "Wow -- so this is the wall separating Melilia from the rest of Morocco," I said, to which he replied, "No -- this is the wall separating Europe from Africa." In Ouijda, on the campus of Mohamed I University itself, there is a camp of sub-Saharan Africans hoping for passage to or through Morocco, and in the hillside forests overlooking Melilia (and apparently also near Ceuta/Septa), there are sub-Saharan Africans who have been in hiding for generations. Thus (among many to be mentioned later) border / migration studies is an area for research collaboration between our two universities, and could include work on human rights (what is the legal status of people living in these semi-permanent transitional encampments?) and the political use of refugees -- Morocco is negotiating free trade status with the EU, and the vigilance it exercises over its borders is a card to be played. When free trade is established in 2012, the contraband traffic across the border with Melilia will adapt or disappear.

The same cannot be said for the black market in gasoline: since Algeria is an oil-producing country, gas is significantly cheaper there than on the other side of the frontier. So for miles and miles along the highway, runners in stolen stripped-down cars ferry gas in 40-litre bidons piled into their trunk and back seat. The prevalence of this contraband gas makes it impossible for regular gas stations to stay in business -- in some towns there simply are none -- and consequently the entire population is dependent on gas trafficking for personal use, mass transit, and agricultural equipment and transport.

The highlight of our stay in northeastern Morocco was an excursion to the Cap des Trois Fourches, a small peninsula which juts out into the Mediterranean near Nador.

The excursion was organized by two members of the science faculty at the University of Mohamed I and had the organizational backing of the local French cultural services. The tour leaders -- a geologist and a biologist -- seemed to have trained in France, and they desribed the mission of their excursions as being the promotion of "la culture scientifique," meaning general knowledge and understanding of science among non-scientists. There were about 20 people on the outing -- high school teachers, a banker, a journalist, a former pilot and his family, some young women in a group, and then L&S&N and their Buffalo guests.

The excursion was brilliantly designed to arouse curiosity about the extraordinary local geological formations at precisely the moment when the desired explanation was available -- JIT Gen Ed, we might say. The same was true for the botany lessons -- the specialization of the biologist was phytopharmaceuticals.

On this wonderfully choreographed excursion I again felt what I have often observed: that in my case, at least, it is not merely linguistic ignorance that travel makes me regret, but ALL my lacunae. Off the coast of Rabat, a few days later, I wandered onto the most extraordinary reef, where in pockets formed millions of years ago -- or so I think -- there now live colonies of sea urchins. How I regretted the incurie of my youth, when I might have learned what I needed to complete my admiration of this enchanting scene.

And history! and economics! I reach to recover what I ever knew of the Almoravids, but alas, there is nothing to remember, for during that lesson, as during so many others, I was not curious to know what the teacher had been assigned to require.

I remember the sidelong exchange of regards narquois among high school classmates when the program of the day was to learn how to read the indicateur du chemin de fer, than which no more ridiculous and futile learning could be imagined by the contemptuous class. Surely proper pedagogy begins by creating or reviving the relevant curiosity. Tired Gen Ed instructors across the disciplines could do worse than to send their students abroad in their first semester to rescue them from a learned indifference.

It is reported that infants are able to discriminate between thousands of sounds, and that the acquisition of language requires us to lose interest in the myriad phonetic nuances we might have cared about in order to notice only those which are phonemic, that is to say, functional. I wonder if this narrowing is assumed to be necessary in all areas of learning... and if the deadening of our curiosity isn't a terrible waste?