Desert theater

The town of Ouarzazate (WAR-zah-zat) lies on the other side of the High Atlas mountains from Marrakesh, a spectacular and hair-raising four-hour bus ride away. When I could remind myself to leave the driving to the CTM driver -- and he was very cautious and competent -- I luxuriated in the scenery. The rock formations alone are in a rich variety of hues, and the vegetation, especially now during the wheat harvest, is gold, deep green, orange, purple, white, and crimson.

Ouarzazate itself is of modest interest. It's the Hollywood of Morocco, with a couple of film studios specializing in desert locations. It also boasts an 18th-century qasbah, the Taouirt Qasbah, which belonged to the Glaoui family, a Berber clan which acquired short-lived wealth and notoriety by collaborating with the French to subdue the rest of the Berbers.

We used Ouarzazate as a launching point for an excursion south into the canyons and desert. Our hotel -- Bab es Sahara (Gateway to the Desert) -- connected us with an agency, and soon we were in a minivan driven by Lhacen, and accompanied by only one other tourist, a Dutchman named Mark, whom the driver called "Hollandi."

It was fortunate that I had decided against renting a car myself, for I would have had to pull over every ten minutes to take photos. The route towards the Dadès Gorge reminded me somewhat of the approach to Petra in that the iron-rich soil is a camaïeu of reds. The interplay of shades with the wide range of geological formations provides a backdrop for the amazing qasbahs which dot the landscape. These are magnificent structures built by Berbers, some dating from the 17th century and perhaps earlier, most now crumbling. In them lived or still live groups of families, and their function, like that of their European analogs, was defensive. In some cases one can see a dramatically perched abandoned qasbah on a peak, with hideous rectangular concrete constructions springing up across the valley. Families are moving out of the qasbahs, explained Lhacen, where everything is "mshrouk" or "communal," in favor of single-family dwellings.

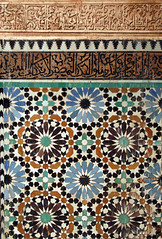

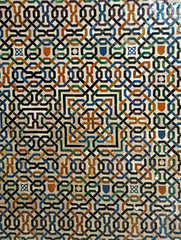

One of our guidebooks complains that the precious work of restoration of these fragile structures is being left haphazardly to private financing, particularly foreign financing, while the Moroccan government appears oblivious to the urgency of timely intervention. I admit to a painful twinge at the prospect of their disappearance, and yet the Moroccan government can scarcely be blamed for prioritizing health care, education, and economic infrastructure -- the city of Buffalo makes the same decision with regard to the grain elevators. Moreover, it seems parochial to assess all responsibility for preservation to the Morrocan nation itself. I remember that after US and coalition forces had allowed the looting of the museum in Baghdad, some reactionary pundit -- I think Ann Coulter -- , declared that it was too bad that "their" museum had been damaged, but that she didn't think any of what was stolen or destroyed was worth the military cost of defending this stragegically insignificant site. Does she not understand that the writing on those stone tablets was part of her history, our history, as well? With decorative patterns of Berber architecture turning up throughout the Islamic world, in Andalusia, in Latin America, what can it mean to say that a restoration project has "foreign" financing?

So we slept in a family-run auberge in the mountains, facing a Berber qasbah called Aït..., and wandered along a mountain stream which alimented family farms. This idyllic existence seemed almost completely free of contact or influence from outside. At one point my son and I wandered a few miles up the road in search of a small store we thought we had seen from the car window. Coming across a group of older people, we inquired. Communication was a bit tricky because for all but the elder of the group, Arabic was as much a foreign language as was French. One of them understood that we were looking for a "supermarché," and said, "We don't have that here in the mountains." When we clarified, they debated among themselves, and at length one of them speculated that there was such a thing two kilometers down the road. She was right, but it was funny to think that for these folks, even very short distances take you into unfamiliar territory.

The next morning we travelled to the Gorges Todra, a deep reddish canyon through which there flows a mountain stream. It is inexpressibly beautiful, both verbally and photographically, since the dramatic contrasts in lighting make it difficult to capture (though of course I tried). Here and for the rest of our excursion, we encountered locals accustomed to commerce with tourists, who had some notion of how to market to our various cultural idiosyncracies.

In the case of Americans, the marketing strategy plays to the value we attach to work -- we are always informed about the intensive hand labor involved in production -- and to what Baudrillard described as a yearning for something real, and a related nostalgia for an imagined bygone era before the triumph of the simulacrum -- a surviving remnant from the reign of the authentic.

These predilections -- shared by European but not Asian, African, or Latin American visitors -- underlie intricate campaigns to which we are statistically receptive. And which the sales force personnel themselves do not always understand: Abdellatif was our guide at the Sekoura Qasbah, costumed for the occasion (though I think invraisemblablement) in the gold-trimmed blue djellabah of the Touareg. He explained the function of rooms and tools, advanced implausible etymologies (the one for misharabia was particularly lame), and pointed to vacant bee hives, whose inhabitants had fallen victim to a local mosquito eradication campaign. Resorting to the tip-enhancing technique of showing the tourist something not on the official circuit, he bade me peek through some slats and see the reconstruction work taking place on an attached structure. "Notice," he said, "that they are using concrete." The government requires that all restoration work be done with the authentic pisé mixture of straw, stones, and mud. But in fact the workers and contractors -- no doubt with tacit official complicity -- are using concrete for the structures, then covering it over with pisé. Similarly, the interlaced palm fronds which traditionally formed the waterproof layer of roofing now serve only to conceal plastic sheeting, which Abdellatif said lasts for ten years. (I wondered what archaeologists would say, centuries from now, about a society which had shunned a cheap, plentiful, durable construction material in favor of some other material whose only advantage was the mysterious value of "authenticity.") After the tour and our tea, we went to rejoin our driver, and caught sight of Abdellatif in jeans and an Ecko tee-shirt speeding away on his motorbike.

As we approached the desert, the touristic enticements became more sophisticated. We saw a demonstration of the khetarra, an underground oasis irrigation system developed in the 17th century and still in use. We were offered various tribal artefacts, fossils, carpets, and drinks. When we reached Erg Chebbi, Moroco's portal to the Sahara sand dunes, we rode on genuine dromadaries and slept in a real nomad tent. But my photos of the setting, below, conceal the concrete/pisé auberge patio where I'm standing and the parking lot behind it.

But as I lay looking up at the very real and vast darkness that night, ignoring the cell phones of our "real" nomad hosts, I thought the sky had not been so brilliantly populated since Camp Marymount. Shooting stars hurtled across the sky into oblivion. And I thought of my favorite Georges Brassens song, Histoire de faussaire, as I let my disbelief evaporate and gave in to the authentic pleasure of pretending.

Se découpant sur fond d'azur

La ferme était fausse bien sûr,

Et le chaume servant de toit

Synthétique comme il se doit.

Au bout d'une allée de faux buis,

On apercevait un faux puits

Du fond duquel la vérité

N'avait jamais dû remonter.

Et la maîtresse de céans

Dans un habit, ma foi, seyant

De fermière de comédie

À ma rencontre descendit,

Et mon petit bouquet, soudain,

Parut terne dans ce jardin

Près des massifs de fausses fleurs

Offrant les plus vives couleurs.

Ayant foulé le faux gazon,

Je la suivis dans la maison

Où brûlait sans se consumer

Un genre de feu sans fumée.

Face au faux buffet Henri-deux,

Alignés sur les rayons de

La bibliothèque en faux bois,

Faux bouquins achetés au poids.

Faux Aubusson, fausses armures,

Faux tableaux de maîtres au mur,

Fausses perles et faux bijoux,

Faux grains de beauté sur les joues,

Faux ongles au bout des menottes,

Piano jouant des fausses notes

Avec des touches ne devant

Pas leur ivoire aux éléphants.

Aux lueurs des fausses chandelles

Enlevant ses fausses dentelles,

Elle a dit, mais ce n'était pas

Vrai, tu es mon premier faux pas.

Fausse vierge, fausse pudeur,

Fausse fièvre, simulateurs,

Ces anges artificiels

Venus d'un faux septième ciel.

La seule chose un peu sincère

Dans cette histoire de faussaire

Et contre laquelle il ne faut

Peut-être pas s'inscrire en faux,

C'est mon penchant pour elle et mon

Gros point du côté du poumon

Quand amoureuse elle tomba

D'un vrai marquis de Carabas.

En l'occurence Cupidon

Se conduisit en faux jeton,

En véritable faux témoin,

Et Vénus aussi, néanmoins

Ce serait sans doute mentir

Par omission de ne pas dire

Que je leur dois quand même une heure

Authentique de vrai bonheur.

Ouarzazate itself is of modest interest. It's the Hollywood of Morocco, with a couple of film studios specializing in desert locations. It also boasts an 18th-century qasbah, the Taouirt Qasbah, which belonged to the Glaoui family, a Berber clan which acquired short-lived wealth and notoriety by collaborating with the French to subdue the rest of the Berbers.

We used Ouarzazate as a launching point for an excursion south into the canyons and desert. Our hotel -- Bab es Sahara (Gateway to the Desert) -- connected us with an agency, and soon we were in a minivan driven by Lhacen, and accompanied by only one other tourist, a Dutchman named Mark, whom the driver called "Hollandi."

It was fortunate that I had decided against renting a car myself, for I would have had to pull over every ten minutes to take photos. The route towards the Dadès Gorge reminded me somewhat of the approach to Petra in that the iron-rich soil is a camaïeu of reds. The interplay of shades with the wide range of geological formations provides a backdrop for the amazing qasbahs which dot the landscape. These are magnificent structures built by Berbers, some dating from the 17th century and perhaps earlier, most now crumbling. In them lived or still live groups of families, and their function, like that of their European analogs, was defensive. In some cases one can see a dramatically perched abandoned qasbah on a peak, with hideous rectangular concrete constructions springing up across the valley. Families are moving out of the qasbahs, explained Lhacen, where everything is "mshrouk" or "communal," in favor of single-family dwellings.

One of our guidebooks complains that the precious work of restoration of these fragile structures is being left haphazardly to private financing, particularly foreign financing, while the Moroccan government appears oblivious to the urgency of timely intervention. I admit to a painful twinge at the prospect of their disappearance, and yet the Moroccan government can scarcely be blamed for prioritizing health care, education, and economic infrastructure -- the city of Buffalo makes the same decision with regard to the grain elevators. Moreover, it seems parochial to assess all responsibility for preservation to the Morrocan nation itself. I remember that after US and coalition forces had allowed the looting of the museum in Baghdad, some reactionary pundit -- I think Ann Coulter -- , declared that it was too bad that "their" museum had been damaged, but that she didn't think any of what was stolen or destroyed was worth the military cost of defending this stragegically insignificant site. Does she not understand that the writing on those stone tablets was part of her history, our history, as well? With decorative patterns of Berber architecture turning up throughout the Islamic world, in Andalusia, in Latin America, what can it mean to say that a restoration project has "foreign" financing?

So we slept in a family-run auberge in the mountains, facing a Berber qasbah called Aït..., and wandered along a mountain stream which alimented family farms. This idyllic existence seemed almost completely free of contact or influence from outside. At one point my son and I wandered a few miles up the road in search of a small store we thought we had seen from the car window. Coming across a group of older people, we inquired. Communication was a bit tricky because for all but the elder of the group, Arabic was as much a foreign language as was French. One of them understood that we were looking for a "supermarché," and said, "We don't have that here in the mountains." When we clarified, they debated among themselves, and at length one of them speculated that there was such a thing two kilometers down the road. She was right, but it was funny to think that for these folks, even very short distances take you into unfamiliar territory.

The next morning we travelled to the Gorges Todra, a deep reddish canyon through which there flows a mountain stream. It is inexpressibly beautiful, both verbally and photographically, since the dramatic contrasts in lighting make it difficult to capture (though of course I tried). Here and for the rest of our excursion, we encountered locals accustomed to commerce with tourists, who had some notion of how to market to our various cultural idiosyncracies.

In the case of Americans, the marketing strategy plays to the value we attach to work -- we are always informed about the intensive hand labor involved in production -- and to what Baudrillard described as a yearning for something real, and a related nostalgia for an imagined bygone era before the triumph of the simulacrum -- a surviving remnant from the reign of the authentic.

These predilections -- shared by European but not Asian, African, or Latin American visitors -- underlie intricate campaigns to which we are statistically receptive. And which the sales force personnel themselves do not always understand: Abdellatif was our guide at the Sekoura Qasbah, costumed for the occasion (though I think invraisemblablement) in the gold-trimmed blue djellabah of the Touareg. He explained the function of rooms and tools, advanced implausible etymologies (the one for misharabia was particularly lame), and pointed to vacant bee hives, whose inhabitants had fallen victim to a local mosquito eradication campaign. Resorting to the tip-enhancing technique of showing the tourist something not on the official circuit, he bade me peek through some slats and see the reconstruction work taking place on an attached structure. "Notice," he said, "that they are using concrete." The government requires that all restoration work be done with the authentic pisé mixture of straw, stones, and mud. But in fact the workers and contractors -- no doubt with tacit official complicity -- are using concrete for the structures, then covering it over with pisé. Similarly, the interlaced palm fronds which traditionally formed the waterproof layer of roofing now serve only to conceal plastic sheeting, which Abdellatif said lasts for ten years. (I wondered what archaeologists would say, centuries from now, about a society which had shunned a cheap, plentiful, durable construction material in favor of some other material whose only advantage was the mysterious value of "authenticity.") After the tour and our tea, we went to rejoin our driver, and caught sight of Abdellatif in jeans and an Ecko tee-shirt speeding away on his motorbike.

As we approached the desert, the touristic enticements became more sophisticated. We saw a demonstration of the khetarra, an underground oasis irrigation system developed in the 17th century and still in use. We were offered various tribal artefacts, fossils, carpets, and drinks. When we reached Erg Chebbi, Moroco's portal to the Sahara sand dunes, we rode on genuine dromadaries and slept in a real nomad tent. But my photos of the setting, below, conceal the concrete/pisé auberge patio where I'm standing and the parking lot behind it.

But as I lay looking up at the very real and vast darkness that night, ignoring the cell phones of our "real" nomad hosts, I thought the sky had not been so brilliantly populated since Camp Marymount. Shooting stars hurtled across the sky into oblivion. And I thought of my favorite Georges Brassens song, Histoire de faussaire, as I let my disbelief evaporate and gave in to the authentic pleasure of pretending.

Se découpant sur fond d'azur

La ferme était fausse bien sûr,

Et le chaume servant de toit

Synthétique comme il se doit.

Au bout d'une allée de faux buis,

On apercevait un faux puits

Du fond duquel la vérité

N'avait jamais dû remonter.

Et la maîtresse de céans

Dans un habit, ma foi, seyant

De fermière de comédie

À ma rencontre descendit,

Et mon petit bouquet, soudain,

Parut terne dans ce jardin

Près des massifs de fausses fleurs

Offrant les plus vives couleurs.

Ayant foulé le faux gazon,

Je la suivis dans la maison

Où brûlait sans se consumer

Un genre de feu sans fumée.

Face au faux buffet Henri-deux,

Alignés sur les rayons de

La bibliothèque en faux bois,

Faux bouquins achetés au poids.

Faux Aubusson, fausses armures,

Faux tableaux de maîtres au mur,

Fausses perles et faux bijoux,

Faux grains de beauté sur les joues,

Faux ongles au bout des menottes,

Piano jouant des fausses notes

Avec des touches ne devant

Pas leur ivoire aux éléphants.

Aux lueurs des fausses chandelles

Enlevant ses fausses dentelles,

Elle a dit, mais ce n'était pas

Vrai, tu es mon premier faux pas.

Fausse vierge, fausse pudeur,

Fausse fièvre, simulateurs,

Ces anges artificiels

Venus d'un faux septième ciel.

La seule chose un peu sincère

Dans cette histoire de faussaire

Et contre laquelle il ne faut

Peut-être pas s'inscrire en faux,

C'est mon penchant pour elle et mon

Gros point du côté du poumon

Quand amoureuse elle tomba

D'un vrai marquis de Carabas.

En l'occurence Cupidon

Se conduisit en faux jeton,

En véritable faux témoin,

Et Vénus aussi, néanmoins

Ce serait sans doute mentir

Par omission de ne pas dire

Que je leur dois quand même une heure

Authentique de vrai bonheur.