On the uses of expressions of courtesy

Arabs learning to function outside the matrix of their language are always grasping for the equivalent of such expressions as "El hamdolillah as-salameh," which is the correct thing to say when someone has come safely to the end of a journey. “So Nawal, I got e-mail from Reham – it seems Ghazi made it ok to Cairo.” “Thank God for safety!”

These expressions are centuries old. When rendered into English, as for example in Richard Burton’s translation of the Thousand and One Arabian Nights, they give a quaint and formal tone to the dialogues. The reader can be so distracted by the overt graciousness, and the contemporary visitor so anxious to participate competently in the exchange of courtesies, that the poetic or ironic exploitation of the rituals can escape our notice. (See Burton, pp?)

It is common to take note of someone’s labor by means of the phrase "Y’atik el ‘aafiah” or “Allah y’atik el ‘aafiah” (“May God grant you rest”). (The second version of the phrase mentions God explicitly, and is more emphatic.) You pronounce the phrase when someone has just finished doing some work, such as carrying something heavy or taking an exam, or when he is in the middle of a task which you are about to interrupt (though in that case a shorter form is used : "El ‘aafieh"). Like the widely familiar pair "Es-salaamu ‘alekum / W’alekum es-salaam," most of these pairs have a somewhat chiasmic (?) construction.

Going native generally makes for smoother relations with local people, who infer from your efforts to convey competence and sophistication that you are not interested in crusader relics, mummy hands, pieces of the true cross, etc. However, as I saw in Damascus, on Wednesday May 24th, at the Firdoos Hotel, going blonde opens up a view on exchanges that would otherwise not be visible.

Me: El ‘aafieh madame...

Hotel desk receptionist: Yes, can I help you?

When her English is better than my Arabic, why persist?

Me: I’m trying to find the Nahas Building on Ahmed Mrewed Street.

HDR: What exactly are you looking for?

Me: I’m looking for AMIDEAST. My hotel sent me in this direction, but nobody I've asked has heard of the building, and there are no street signs.

HDR makes a phone call to a colleague ("El 'aafieh Sawsan..."), then summons the lethargic bellhop. Their exchange is in Arabic:

HDR: This lady wants to take the street over by the pharmacy to the next block and then left at the first traffic light. Would you please escort her part of the way.

Bellhop: Me?? Go with her? But I am the only one on duty. I can’t.

HDR: It would only take you a second, and if any hotel guests were coming or going you wouldn’t be missing them. But never mind. I see that you don’t want to.

Bellhop: Ok, ok. What do you want me to do, exactly?

HDR: Nothing. Never mind. You may leave now.

Bellhop: ...

HDR: Right now.

Bellhop: ...

HDR: And may God grant you rest.

* * * * * *

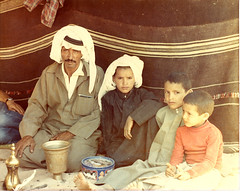

So Ghazi headed south through the long Jordanian desert to Aqaba, where after interminable delays he caught a ferry which carried him across the Red Sea and into Egypt, after which another bus brought him to Cairo. Meanwhile, I was in a service (ie group) taxi riding north and east to Beirut.

There have been a few changes in the border crossing from Jordan to Syria -- now the chassis of all cars entering Syria has to be dipped in some kind of antiseptic bath, and that’s apparently a precaution against avian flu. But the basics are still the same – huge dingy halls crowded with flies and travellers and staffed by legions of bored functionaries wasting their lives in an Ottoman-era bureaucracy. Resisting the evidence of the sheer futility of their stultifying activity, the border guards frown sternly at your paperwork, call their associates over to scrutinize some detail of your visa application, demand suspiciously your place of birth and the nature of your work. When they have exhausted your entertainment potential, they let you go. The most important rule of border crossings is to avoid giving rise to any hope of diversion. Travellers who make scenes are doomed. They will not be released until every last tear, every last hysterical jeremiade, and every last enraged imprecation have been depleted. A traveller who arrives already limp is processed quickly.

The road from Damascus to Beirut is dramatic. You wind through mountains, getting a glimpse of the Mediterranean every now and then as well as views of villages and towns at every altitude. The driving is terrifying, but I think only because it violates so many of the rules we are accustomed to and thus appears lawless. My guess is that most of the drivers run that route frequently and know its codes.

Beirut is splendid. The people are very friendly. One sees evidence everywhere of the determination to rebuild the city. The physical reconstruction is advancing in parallel with a visible campaign to rebuild social ties across divisions, but ironically, the two campaigns are not necessarily in sync. For example, to many Beirutis, the reconstruction of a large part of downtown, right by the Corniche and just south of Martyrs' Square, has produced a result that is almost Disneyesque (think "Lebanon Land" at Disney World). The area (called "Solidere") is a wonderful commercial success and is brimming with consumers all the time. Foreign currencies are accepted in every shop in this area, and every restaurant brings every customer a bill where the total is expressed in both Lebanese pounds and US dollars. The area has several American chain outlets, such as Starbucks.

Further inland, another neighborhood is being aggressively restored. The results are visually pleasing, no doubt. But some complain that an opportunity to do something new and bold has been squandered in deference to an ideology of slavishly faithful restoration. Bernard Khoury, a RISD and Harvard graduate, is among those clamoring for, and creating, something new. One of his controversial (re)creations is called "Centrale," a war-torn building whose bullet-riddled exterior he has wrapped in a mesh-like exoskeleton, and which is now one of Beirut's most fashionable nightlife destinations.

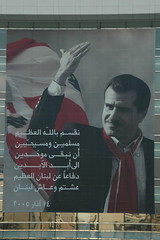

The main proponent of the rebuilding effort was the late Rafiq Hariri, whose image appears everywhere in the city, and for whom there is an immense temporary shrine off Martyrs' Square. A Hariri ally and vocal critic of Syria, Gibran Tueni, editor of the progressive daily En-Nahar, was also assassinated. His calls for unity are seen in posters throughout the area surrounding the newspaper headquarters.

More about Beirut, then on to Damascus, in the next installment.