Unit 3: Do the Interests of Others Matter?

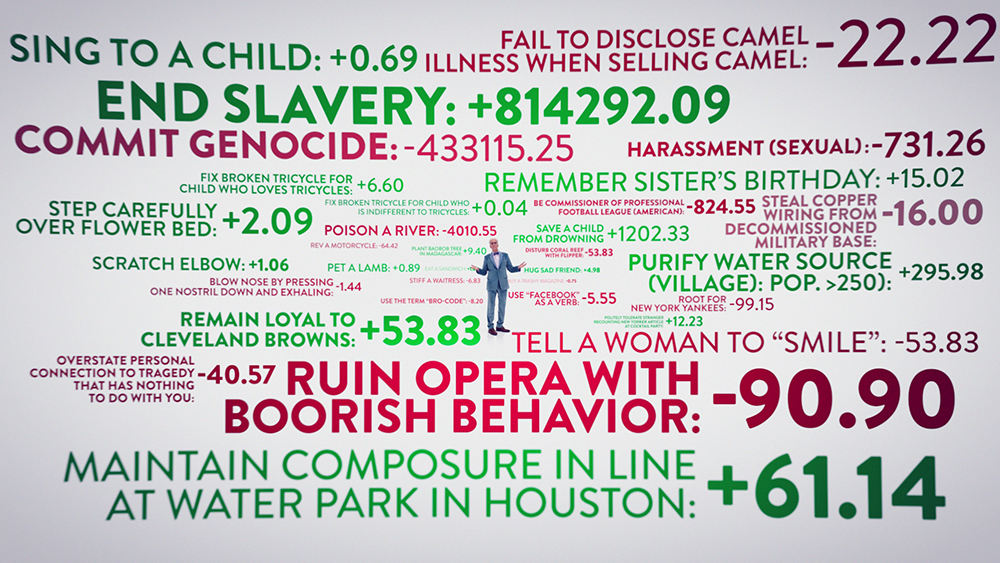

Photo: Drew Goddard / NBC.

If you do want to be responsive to the interests of others, how exactly should you act? The ethical theory of Classical Utilitarianism provides a deceptively simple principle: promote the greatest good for the greatest number. Of course, the devil is in the details, where Utilitarianism must clearly specify what it meant by this greatest good and how you should go about promoting it. This module will help explain those, and other, details.

In order to accomplish that, we have three learning outcomes. By the end of this module, you will be able to…

- Describe the various elements of Jeremy Bentham’s Classical Utilitarianism,

- Summarize how the Hedonism of Classical Utilitarianism may justify its concern for the well-being of all sentient life, and

- Apply Bentham’s “Felicific Calculus” for measuring the morality of your decisions.

Read This:

|

An Introduction Concerning the Principles of Morals and Legislation

|

The Revolution in Ethics

|

The Classical Version of the Theory

|

Context

Jeremy Bentham (1748—1832) was a British philosopher who argued that happiness alone has intrinsic value, and that the fundamental moral obligation of a person is to produce as much happiness as they can.

But here the focus is not just on your own happiness; rather, in the famous Utilitarian phrase, “everybody to count for one, nobody for more than one” (John Stuart Mill, whom we will read in Module 18, attributes this phrase to Bentham, though it does not seem to appear in any of Bentham’s publications). This places priority on achieving the “greatest happiness of the greatest number” (Bentham, 1789/2003, p. 20), another Utilitarian motto, and thus locates the virtue of beneficence at the heart of ethics. In particular, Bentham advocates a form of Utilitarianism that equates happiness with pleasure and the absence of pain.

Today, Bentham’s theory is now known as Classical Utilitarianism, which makes the following claims about morality:

- Consequentialism: The overall goodness of outcomes (that is, the goodness of the outcomes for everyone affected by those outcomes) is the only thing with intrinsic moral value.

- Welfarism: The overall goodness of an outcome is measured solely by the well-being of everyone affected.

- Hedonism: Well-being is nothing other than “happiness”, understood as pleasure and absence of pain.

-

The Total View, which has three claims:

4a. Quantitative Monism: Individual well-being is measured numerically, and specifically, by one numerical quantity. This quantity is usually called Utility. 4b. Sum Ranking: Overall well-being is the aggregate utility for the group. This involves two claims: i. Each person in the group has an individual utility value associated with their own personal well-being, and ii. The aggregate utility for the group is calculated by summing up these individual utilities. 4c. Optimization: More aggregate utility is always better than less aggregate utility.

Do not panic if this all looks frightening to you!

I will walk you through all of this during my videos. The most important thing to focus on when reading Bentham is how he understands and measures “happiness”. You should also reflect on why Bentham believes this is the proper foundation for all of morality. Do that, and you will be surprised how the complex seeming elements of his Classical Utilitarianism all fit together.

The readings from James Rachels and Stuart Rachels provide some context and help flesh out the basic claims made by Utilitarians.

Reading Questions

As you read, keep these questions in mind:

- How does Jeremy Bentham justify that happiness, understood as pleasure and absence of pain, is the proper foundation of all ethics and morality?

- How would you formulate Bentham’s “calculus” of pleasures that a person is supposed to use when making a decision?

- Bentham’s “circumstance” of “extent” (1789/2003, p. 42) maintains that a person’s actions should be evaluated by the pleasure of all affected, and not only the amount of pleasure that person receives by performing it. What reasons could Bentham have to reject Ethical Egoism?

- What are the primary features of Classical Utilitarianism, according to James Rachels and Stuart Rachels? How are these related to the features of Classical Utilitarianism that I have given you?

Although I strongly suggest that you write out brief answers to these questions, you do not have to turn in written responses. You do, however, need to be prepared to answer questions like these on module quizzes and the unit exams.

References

Bentham, J. (2003). An introduction concerning the principles of morals and legislation. In M. Warnock (Ed.), Utilitarianism and On liberty: Including Mill’s ‘Essay on Bentham’ and selections from the writings of Jeremy Bentham and John Austin (2nd ed., pp. 17—51). Blackwell. (Original work from 1789)

Rachels, J., & Rachels, S. (2018). The revolution in ethics. In The elements of moral philosophy (9th ed., pp. 101—102). McGraw-Hill.

Rachels, J., & Rachels, S. (2018). The classical version of the theory. In The elements of moral philosophy (9th ed., pp. 118—119). McGraw-Hill.

Watch This:

|

Video 1

|

Video 2

|

|

Video 3

|

Video 4

|

Do This:

|

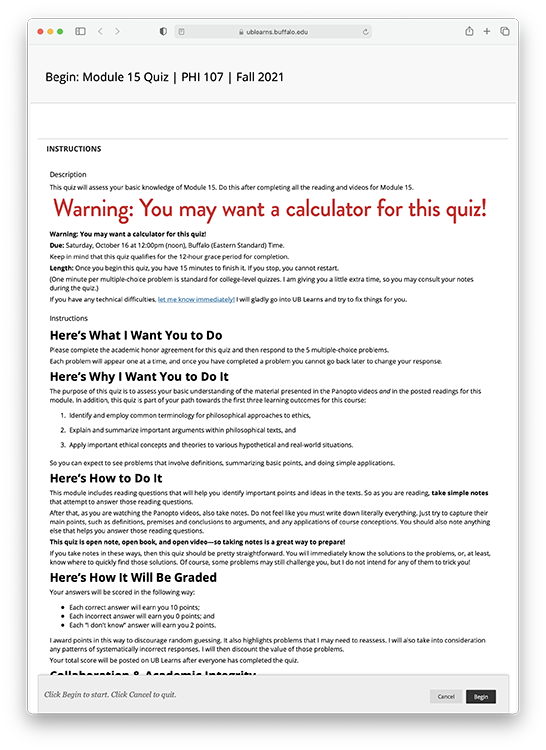

Module 15 Quiz

Due: October 16 |

|

|

5 Tweets this Week

Due: October 16 |

|

|

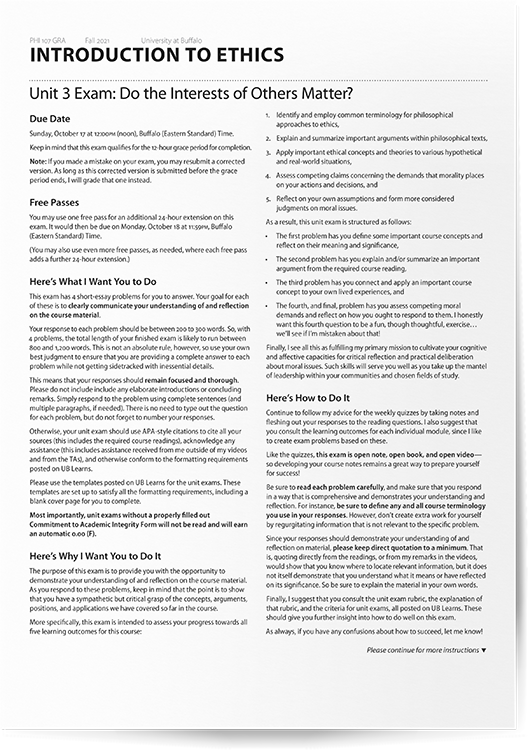

Unit 3 Exam

Due: October 17 |

|

Submit the Unit 3 Exam here! |