Unit 4: Utilitarianism & Its Limits

Photo: Morgan Sackett / NBC.

As we have seen, the Hedonism of Classical Utilitarianism leaves it vulnerable to a variety of criticism. The influential Utilitarian thinker John Stuart Mill was definitely aware of aware of these problems, and so he sought to articulate a much richer notion of human happiness and pleasure. This leads to what we might consider a Deliberative Utilitarianism.

We have four learning outcomes for this module. At the end of it, you will be able to…

- Compare and contrast the different forms of Utilitarianism coming from Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill,

- Reflect on your own nature as a progressive being along with the sorts of pleasures that might make available for you,

- Apply the Pluralistic Total View to examples of decision making, and

- Assess whether you would trust Mill’s Test of the Cognoscenti.

Read This:

|

What Utilitarianism Is

|

Context

Like Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) is a Utilitarian who argues that happiness alone has intrinsic value, and that the fundamental moral obligation of a person is to produce as much happiness as they can. (In fact, Mill’s father was extremely close friends with Bentham, and so Mill was Bentham’s godson.)

Unlike Bentham, however, Mill maintains that the quality (or type) of the happiness produced is far more important than its simple quantity (or amount). More pleasure is not always better. Instead certain pleasures (even if in lesser amounts) may be more valuable to the extent that they come from the cultivation and exercise of the higher-order faculties possessed by humans. This means that Mill’s conception of pleasure and happiness is radically different from that defended by Bentham, leading Mill’s theory to diverge in some important ways from Classical Utilitarianism.

Mill’s theory might then be called Deliberative Utilitarianism, and it consists of the following claims:

- Consequentialism: The overall goodness of outcomes (that is, the goodness of the outcomes for everyone affected by those outcomes) is the only thing with intrinsic moral value.

- Welfarism: The overall goodness of an outcome is measured solely by the well-being of everyone affected.

- Eudaimonism: Well-being is nothing other than “happiness”, understood as the pleasure that comes from the cultivation and exercise of those higher-order capacities distinguishing human beings from other animals.

-

The Pluralistic Total View, which has three claims:

4a. Quantitative Pluralism: Individual well-being is measured numerically, and specifically, by a vector of numerical quantities. This vector may be called a vector of Plural Utilities. Some utilities in this vector have priority over others. That is, there are some utilities that are more valuable than other utilities. 4b. Vector Sum Ranking: Overall well-being is the vector of aggregate utility for the group. This involves two claims: i. Each person in the group has an individual vector of plural utilities associated with their own personal well-being, and ii. The vector of aggregate utility for the group is calculated by summing up these individual vectors of plural utilities. 4c. Lexical Priority: Optimize according to the highest-level (most valuable) utilities in the vector of plural utilities. If there are ties, then optimize according to the second-highest-level (second most valuable) utilities to break those ties. If ties remain, optimize according to the third-highest-level utilities, and so on. Apart from breaking ties, no lower-level (less valuable) utilities may outweigh or override higher-level ones.

While (1) and (2) are shared with Classical Utilitarianism, (3) marks a major departure that requires complex modifications to the other conditions.

Do not panic if this all looks frightening to you!

I will walk you through all of this during my videos. The important thing to focus on when reading Mill is how he understands “happiness” in terms of quality (not quantity) of pleasure and justifies this view. Do that, and you will be surprised how the complex seeming elements of Deliberative Utilitarianism all fit together.

Reading Questions

As you read, keep these questions in mind:

- How would you describe John Stuart Mill’s conception of happiness? How does it differ from Jeremy Bentham’s?

- In his discussion of pleasure, Mill repeatedly claims that pleasures can be distinguished by quality and well as quantity. What justifies this qualitative distinction of higher and lower pleasures? How does this distinction explain Mill’s famous claim that “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied” (1861/2003, p. 188)?

- Mill also gives a test appealing to “competent judges” (1861/2003, p. 189) by which pleasures can be separated into higher and lower kinds. Today this is known as the Test of the Cognoscenti. How is this supposed to work? Why should we (who are not competent judges) trust in the results of this test?

Although I strongly suggest that you write out brief answers to these questions, you do not have to turn in written responses. You do, however, need to be prepared to answer questions like these on module quizzes and the unit exams.

References

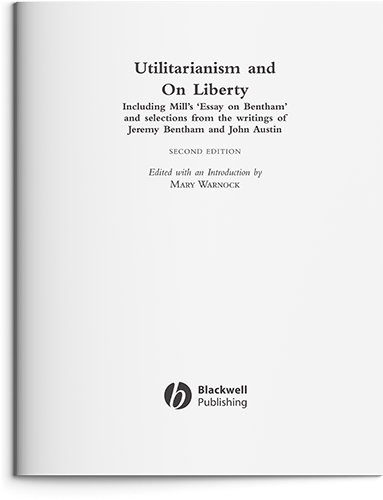

Mill, J. S. (2003). What utilitarianism is [Chapter 2 from Utilitarianism]. In M. Warnock (Ed.), Utilitarianism and On liberty: Including Mill’s ‘Essay on Bentham’ and selections from the writings of Jeremy Bentham and John Austin (2nd ed., pp. 185–202). Blackwell. (Original work from 1861)

Watch This:

|

Video 1

|

Video 2

|

|

Video 3

|

Video 4

|

|

Video 5

|

Do This:

|

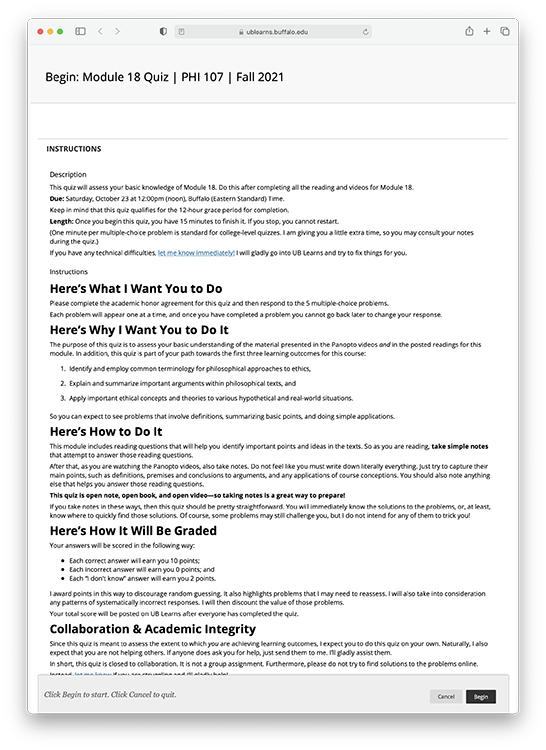

Module 18 Quiz

Due: October 23 |

|

|

5 Tweets this Week

Due: October 23 |