Love and commerce in the Middle East

Among the rigorous competitive local sports for which American visitors are least prepared are those surrounding the buying and selling of goods and services. (Another is street survival, where one competes in two leagues: pedestrian vs. vehicular and inter-vehicular.) When a bargain hunter comes away from the souq pleased with his haggling skills, we can be sure that he is not nearly so pleased as the merchant. Accustomed to standing by slack-jawed while the scanner totals our purchases and siphons money from our account, we Americans are utterly unprepared for the Middle Eastern shopping experience.

There is something initially offensive to American instincts about variation in prices when applied to individual consumers. We don’t cry foul when inner-city grocery stores charge more for milk than suburban supermarkets, but charging everybody at the store the same price – a price which is known and accepted in advance – seems to us the only fair and democratic way to do business. There is no getting around the fact that this is a difficult cultural adjustment for us to make, but a moment’s reflection makes it obvious that the merchants and taxi drivers in the world’s oldest center of trade and commerce are simply applying at a more granular level the same free market principles that we advocate: the price of an item or a service is what a buyer is willing to pay and what a seller is willing to accept. It is also essential to the Middle Eastern version that everyone leave happy, since merchants want customers to come back and bring their friends. This is why I prefer to think of the transaction as sport rather than combat.

Advertising targeted to individual consumers on the basis of the purchases they make through loyalty or credit cards, the websites they visit and even the words they use in their e-mail (à la G-mail) makes us shudder at the erosion of privacy. But as I discovered here two decades ago, “privacy” is a recent and fragile construct. Everybody knows your business, whether the information travels via cybernetwork or from one coffee drinker to another. Middle Eastern merchants are not wired to any database, but they evaluate you precisely using the vast amount of data which you freely emit. Long before they answer your question “How much for this piece?”, they have noted the language you speak as well as the volume and accompanying gesticulation; they have studied your apparel, haircut, shoes, gait and demeanor to determine what country you’re from and what social stratum you inhabit; they determine whether it is you or your companion who decides on expenditures and whether you have already acquired any objects during this foray and if so from where; from the objects which attract your gaze and the questions you ask, they learn which religion you belong to and what is your degree of fervor. Whether yours is the faith of the prophets or that of the organic farmers or that of the liberation freedom fighters, your consumer proclivities and susceptibilities will have been calculated. The advantage of their data mining over our anonymous automated system is, to my taste, the sporting human interface. Versus Wegman's, I have no chance; here, I might win a round or two.

It is entertaining to watch the system adapt to confusing signals, such as those which we three emit when travelling together. Reham has gone completely native and has actually been able to get into various archaeological sites at the Egyptian rate. Ghazi greets people in Arabic, but his punk/urban appearance (wild hair, sagging pants) is irreconcilable with either of the two hypotheses through which his presence might be explained, since that look does not suggest leisure travel and would not normally be tolerated by an Arab parent. Apparently I am emitting signals that seem more German or British or Canadian than American, because it usually takes the merchants four or five guesses to get it right.

I bought a towel at the Khan el khalili before leaving Cairo. Our negotiations had reached a certain price that was still higher than what I wanted to pay, but which apparently my data profile encouraged the merchant to expect. He made a move which looked like a time-out, a way of avoiding stalemate:

Merchant: Ma sha’ Allah, your husband is a very lucky man!

Me: More than you imagine! We are divorced.

Merchant: Not possible! How can this be?!

Me: Believe it.

Merchant: Wa Allahi, I shall marry you.

Me: No kidding?! So then the towel would be free?

Merchant: Yes, a thousand towels. And more!

What I had taken to be a time-out was of course the end game, since the charming incongruity of the marriage proposal disarmed my aggressive shopper strategy.

However flattered I was to know that, at my advanced age, I could still fetch a thousand towels, this was nothing next to the offers coming in for Reham’s hand. So far the most lucrative proposal was one we received in Luxor, in the Valley of the Kings, where with no disrespect for Reham’s beauty I must say that the luxury of the royal burials may possibly have had an inflationary effect. Personally, I was ready to sign off on the two million camel proposal, but Reham objected that the suitor kept changing the terms, and Ghazi, as the ranking male, wanted to hold out for a seaside villa for the family. I think we were too hasty in declining these offers – a nice Red Sea vacation home, where we’d never want for towels, was surely within our grasp.

In the Middle East, as in America, art and commerce are also bedfellows. Here is a photo (below) I shot from a car riding north out of Beirut towards the mountains.

Reham explained to me that the featured spokesmodel, fabulously popular Lebanese singer Nancy Ajram, stars in a music video which, by an amazing coincidence, began as a Coke commercial. The song’s catchy refrain is productively ambiguous: “Ana mish aiza illa hua,” which in the commercial means “I don’t want anthing but it [Coke]” whereas in the music video, the pronoun would be translated as “him,” so something like, “I only want him, nobody else.” It goes without saying that every airing of the song or video reinforces the Coke marketing message and adds up to priceless free advertising. It seems unavoidably obvious that Coke “made” Nancy, but that will have to be a subject for further inquiry. By the way, a rival pop star is the spokesmodel for, you guessed it, Pepsi.

All of which brings me a restaurant in Amman where I was sent by friends at AMIDEAST. I was in search of a dish called “frika,” which is basically wheat harvested while it is still a bit green and then smoked. (You can take the girl out of the south...) It is the most amazing taste, but for some reason (it doesn’t go well with Coke?), it is difficult to find. It figures on the menu of Rim el Bawadi, which is why my friends sent me there.

Rim el Bawadi is a very new restaurant situated in the poshest of the new outer-ring neighborhoods of Amman, a city whose explosive growth is partly due to Iraqis who buy land there (paying in cash with dollars) and largely, surely, to enormous American investment. The restaurant has a lot going for it: the food is good and reasonably priced, there are seemingly hundreds of tables in a variety of open-air rooms staffed by eager waiters, and there is a play area for children. But the most striking thing about the restaurant is its conspicuously artificial “Arab” identity. Rim el Bawadi is an Arab restaurant which is pretending not to be Continental or American, but pretending to be Arab. Despite its address in the capital of an Arab country, not an iota of its lavish “Arab” decor is or is meant to appear authentic. There are Bedouin artifacts everywhere, but they are displayed incongruously in decors which are of vague Damascene or Ottoman or Egyptian inspiration. Waiters scurry about dressed up as Bedouins, but they themselves are Egyptians (as are virtually all waiters in Jordan) and they don’t know how to pour the coffee in the famously Bedouin way. Near the children’s play area, there is a brightly lit photo studio where diners can dress up as Bedouins and have their photo taken. Now if this were at Disney World and the people dressing up were from Wisconsin, that would be one thing – “Have a real desert experience without all that tiresome sand!” But the people here dressing up as Bedouins are not foreigners, they are Arabs, they are the Jordanians who live in Abdoun and Shmeisani, and whose grandparents or greatparents themselves lived in or near the desert. By their eager participation in this simulacrum, they seem to be putting distance between themselves and the ancestral traditions in which the West has been too eager to freeze them. It is easy to sympathize with their impatience to be recognized as a modern society, especially given the political and economic cost of being classed as “developing,” but to watch modern Jordan cannibalize the ancient Bedouin traditions is amazingly sad, to say nothing of the dubious superiority of the MODERN LIFESTYLE which is effacing them.

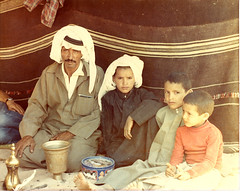

As for the actual Bedouins, I had mentioned in an earlier post that we would try to find the family of the Bedouin guide thanks to whose intimate familiarity with the desert I was first able to see the amazing spetacle of Wadi Rum. When the kids and I travelled there this week, we did not see Abu Salem (= father of Salem) and his family, but when we gave the photos to the Bedouin guides we did meet, we got news of them. It seems that the father, Abu Salem, had died many years ago. Also the youngest son, Mohammad, had died in a car accident – a 4WD had flipped over. The second son, Eid, had married and had children and was still living in the area. Salem, the oldest, is director of customs at the port of Aqaba.

I had been afraid that I would find Salem and his brothers working as barristas at the Wadi Rum Starbucks, or that I wouldn’t be able to find any trace of them at all. It is good to know that the family is still part of the desert, still custodians of a spectacular treasure, but even this vestigial presence seems doomed to disappear. The government now pays Bedouin families to build houses and settle down, and the legendary desert patrol is now conducted via 4WD rather than camel. The lure of city jobs or military careers pulls many of them away. Seeing the traditions disappear over time is a bit like looking at the ornately sculpted façades of Petra which, through time and erosion, are receding back into the flat surface of the sandstone from which they were so painstakingly carved two millenia ago.

If I were to produce an illustrated lexicon, the word “ineffable” would be illustrated by images of Wadi Rum and Petra.

It is humbling for a wordsmith to be confronted with the utter inadequacy of language to convey even the feeblest notion of their spectacular and dreamlike beauty. To visit these holy places again was an unhoped for blessing; to visit them with my children, escorted by the next generation of Bedouin guides, was a transcendent experience.

We took many photos of the landscape, of the prehistoric inscriptions, and of Mousa, our 17-year-old guide. Ghazi fell so in love with the place that I know for certain he will return. When he does, he'll bring these photos back with him. If the human race is lucky, Ghazi will find Mousa and his family there at Wadi Rum, and not working at Rim el Bawadi.

There is something initially offensive to American instincts about variation in prices when applied to individual consumers. We don’t cry foul when inner-city grocery stores charge more for milk than suburban supermarkets, but charging everybody at the store the same price – a price which is known and accepted in advance – seems to us the only fair and democratic way to do business. There is no getting around the fact that this is a difficult cultural adjustment for us to make, but a moment’s reflection makes it obvious that the merchants and taxi drivers in the world’s oldest center of trade and commerce are simply applying at a more granular level the same free market principles that we advocate: the price of an item or a service is what a buyer is willing to pay and what a seller is willing to accept. It is also essential to the Middle Eastern version that everyone leave happy, since merchants want customers to come back and bring their friends. This is why I prefer to think of the transaction as sport rather than combat.

Advertising targeted to individual consumers on the basis of the purchases they make through loyalty or credit cards, the websites they visit and even the words they use in their e-mail (à la G-mail) makes us shudder at the erosion of privacy. But as I discovered here two decades ago, “privacy” is a recent and fragile construct. Everybody knows your business, whether the information travels via cybernetwork or from one coffee drinker to another. Middle Eastern merchants are not wired to any database, but they evaluate you precisely using the vast amount of data which you freely emit. Long before they answer your question “How much for this piece?”, they have noted the language you speak as well as the volume and accompanying gesticulation; they have studied your apparel, haircut, shoes, gait and demeanor to determine what country you’re from and what social stratum you inhabit; they determine whether it is you or your companion who decides on expenditures and whether you have already acquired any objects during this foray and if so from where; from the objects which attract your gaze and the questions you ask, they learn which religion you belong to and what is your degree of fervor. Whether yours is the faith of the prophets or that of the organic farmers or that of the liberation freedom fighters, your consumer proclivities and susceptibilities will have been calculated. The advantage of their data mining over our anonymous automated system is, to my taste, the sporting human interface. Versus Wegman's, I have no chance; here, I might win a round or two.

It is entertaining to watch the system adapt to confusing signals, such as those which we three emit when travelling together. Reham has gone completely native and has actually been able to get into various archaeological sites at the Egyptian rate. Ghazi greets people in Arabic, but his punk/urban appearance (wild hair, sagging pants) is irreconcilable with either of the two hypotheses through which his presence might be explained, since that look does not suggest leisure travel and would not normally be tolerated by an Arab parent. Apparently I am emitting signals that seem more German or British or Canadian than American, because it usually takes the merchants four or five guesses to get it right.

I bought a towel at the Khan el khalili before leaving Cairo. Our negotiations had reached a certain price that was still higher than what I wanted to pay, but which apparently my data profile encouraged the merchant to expect. He made a move which looked like a time-out, a way of avoiding stalemate:

Merchant: Ma sha’ Allah, your husband is a very lucky man!

Me: More than you imagine! We are divorced.

Merchant: Not possible! How can this be?!

Me: Believe it.

Merchant: Wa Allahi, I shall marry you.

Me: No kidding?! So then the towel would be free?

Merchant: Yes, a thousand towels. And more!

What I had taken to be a time-out was of course the end game, since the charming incongruity of the marriage proposal disarmed my aggressive shopper strategy.

However flattered I was to know that, at my advanced age, I could still fetch a thousand towels, this was nothing next to the offers coming in for Reham’s hand. So far the most lucrative proposal was one we received in Luxor, in the Valley of the Kings, where with no disrespect for Reham’s beauty I must say that the luxury of the royal burials may possibly have had an inflationary effect. Personally, I was ready to sign off on the two million camel proposal, but Reham objected that the suitor kept changing the terms, and Ghazi, as the ranking male, wanted to hold out for a seaside villa for the family. I think we were too hasty in declining these offers – a nice Red Sea vacation home, where we’d never want for towels, was surely within our grasp.

In the Middle East, as in America, art and commerce are also bedfellows. Here is a photo (below) I shot from a car riding north out of Beirut towards the mountains.

Reham explained to me that the featured spokesmodel, fabulously popular Lebanese singer Nancy Ajram, stars in a music video which, by an amazing coincidence, began as a Coke commercial. The song’s catchy refrain is productively ambiguous: “Ana mish aiza illa hua,” which in the commercial means “I don’t want anthing but it [Coke]” whereas in the music video, the pronoun would be translated as “him,” so something like, “I only want him, nobody else.” It goes without saying that every airing of the song or video reinforces the Coke marketing message and adds up to priceless free advertising. It seems unavoidably obvious that Coke “made” Nancy, but that will have to be a subject for further inquiry. By the way, a rival pop star is the spokesmodel for, you guessed it, Pepsi.

All of which brings me a restaurant in Amman where I was sent by friends at AMIDEAST. I was in search of a dish called “frika,” which is basically wheat harvested while it is still a bit green and then smoked. (You can take the girl out of the south...) It is the most amazing taste, but for some reason (it doesn’t go well with Coke?), it is difficult to find. It figures on the menu of Rim el Bawadi, which is why my friends sent me there.

Rim el Bawadi is a very new restaurant situated in the poshest of the new outer-ring neighborhoods of Amman, a city whose explosive growth is partly due to Iraqis who buy land there (paying in cash with dollars) and largely, surely, to enormous American investment. The restaurant has a lot going for it: the food is good and reasonably priced, there are seemingly hundreds of tables in a variety of open-air rooms staffed by eager waiters, and there is a play area for children. But the most striking thing about the restaurant is its conspicuously artificial “Arab” identity. Rim el Bawadi is an Arab restaurant which is pretending not to be Continental or American, but pretending to be Arab. Despite its address in the capital of an Arab country, not an iota of its lavish “Arab” decor is or is meant to appear authentic. There are Bedouin artifacts everywhere, but they are displayed incongruously in decors which are of vague Damascene or Ottoman or Egyptian inspiration. Waiters scurry about dressed up as Bedouins, but they themselves are Egyptians (as are virtually all waiters in Jordan) and they don’t know how to pour the coffee in the famously Bedouin way. Near the children’s play area, there is a brightly lit photo studio where diners can dress up as Bedouins and have their photo taken. Now if this were at Disney World and the people dressing up were from Wisconsin, that would be one thing – “Have a real desert experience without all that tiresome sand!” But the people here dressing up as Bedouins are not foreigners, they are Arabs, they are the Jordanians who live in Abdoun and Shmeisani, and whose grandparents or greatparents themselves lived in or near the desert. By their eager participation in this simulacrum, they seem to be putting distance between themselves and the ancestral traditions in which the West has been too eager to freeze them. It is easy to sympathize with their impatience to be recognized as a modern society, especially given the political and economic cost of being classed as “developing,” but to watch modern Jordan cannibalize the ancient Bedouin traditions is amazingly sad, to say nothing of the dubious superiority of the MODERN LIFESTYLE which is effacing them.

As for the actual Bedouins, I had mentioned in an earlier post that we would try to find the family of the Bedouin guide thanks to whose intimate familiarity with the desert I was first able to see the amazing spetacle of Wadi Rum. When the kids and I travelled there this week, we did not see Abu Salem (= father of Salem) and his family, but when we gave the photos to the Bedouin guides we did meet, we got news of them. It seems that the father, Abu Salem, had died many years ago. Also the youngest son, Mohammad, had died in a car accident – a 4WD had flipped over. The second son, Eid, had married and had children and was still living in the area. Salem, the oldest, is director of customs at the port of Aqaba.

I had been afraid that I would find Salem and his brothers working as barristas at the Wadi Rum Starbucks, or that I wouldn’t be able to find any trace of them at all. It is good to know that the family is still part of the desert, still custodians of a spectacular treasure, but even this vestigial presence seems doomed to disappear. The government now pays Bedouin families to build houses and settle down, and the legendary desert patrol is now conducted via 4WD rather than camel. The lure of city jobs or military careers pulls many of them away. Seeing the traditions disappear over time is a bit like looking at the ornately sculpted façades of Petra which, through time and erosion, are receding back into the flat surface of the sandstone from which they were so painstakingly carved two millenia ago.

If I were to produce an illustrated lexicon, the word “ineffable” would be illustrated by images of Wadi Rum and Petra.

It is humbling for a wordsmith to be confronted with the utter inadequacy of language to convey even the feeblest notion of their spectacular and dreamlike beauty. To visit these holy places again was an unhoped for blessing; to visit them with my children, escorted by the next generation of Bedouin guides, was a transcendent experience.

We took many photos of the landscape, of the prehistoric inscriptions, and of Mousa, our 17-year-old guide. Ghazi fell so in love with the place that I know for certain he will return. When he does, he'll bring these photos back with him. If the human race is lucky, Ghazi will find Mousa and his family there at Wadi Rum, and not working at Rim el Bawadi.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home