Us and them

One of the alternative lives I’ve always wanted to lead is that of the analyst of political uses of images. What a fun subject! It may be that you have to do the intro course in a country other than your own. At any rate, I know that until I had taken the Middle East immersion version, I was oblivious to American stagings.

So in Jordan, as previously mentioned, one frequently sees an image showing the late King Hussein in a warm and friendly pose, sitting with his son and heir King Abdullah. In Syria you see a montage consisting of an image of the late Hafez el-Asad next to an image of his son and heir, Bashar el-Asad. There is sometimes a third face, that of the president's brother -in-law who happens to be the chief of military intelligence, and who was implicated in the assassination of Rafiq Hariri.. Perhaps because Syria was for so long in the Soviet orbit, the tone of the imagery is more severe; there is no grinning; it is not warmth and happiness being conveyed, but rather raw power. Not “Love me, love my son,” as in Jordan, but rather “Remember how I kicked your ass? Well! You ain’t seen nothin yet!” An enormous gilded bust of Hafez el-Asad at the entrance to the military museum in Damascus is particularly communicative.

In Beirut, in contrast, emotions and political impulses are manipulated via the imagery of martyrdom. Given the decades of civil war, each faction has a long roster of fallen heroes, and recent violence has only made the lists longer. What I don’t know, and couldn’t know without a vastly better grasp of local politics, is the precise agenda for which the images are being exploited. It is obvious enough to surmise that the ubiquitous and larger-than-life images of Hariri and Tueni are fronting a campaign to rid Lebanon of Syrian influence. But there is surely more to it than that. I am curious to know whether the Hariri-Tueni support for rebuilding and modernization was offensive to those who considered that traditional values were being swept away in a rush to become a client state of America and the West, or those who thought that the coercive rhetoric about unity foreclosed a full airing of grievances, or those who thought something else altogether.

Apropos only vaguely of all this, there is an interesting commercial running on MBC2, a satellite TV station which plays American movies with Arabic subtitles 24/7 throughout the region. The commercial shows an Arab woman in a modern house wearing a headscarf and modest dress. She wants to serve orange juice, but is struggling, poor dear, what with the oranges rolling everywhere, and having to wield the big knife and the juicer, and OMG, did she just break a nail? She throws up her hands, and behold, a gleaming two-liter jug of made-from-concentrate orange juice appears magically on her counter, ready to be served to guests. Message: our product is compatible with your traditional values of modesty and hospitality, and if you’re ever going to have LIFESTYLE, you don’t have time to make your own orange juice.

Now we’re all for liberating people from back-breaking demeaning tasks all over the world, and no doubt I have pension stocks in Nestle or whatever multinational is pimping its juice to folks over here. But speaking as someone raised on the miracle of canned food in the 50s, I remember what a revelation it was to taste fresh asparagus, green beans, and chow mein.

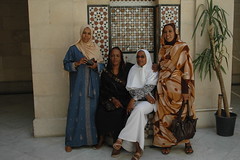

Which brings me to the question of what it is that we’re looking for when we come over here. I come to this question via the ethical issue of photography here, where every published image of an exoticized other reinforces stereotypes of Arab backwardness and by implication the natural right of the superior civilization to help itself to local resources. On the other hand, if we suspend consciousness of the staggering economic imbalance separating our worlds, it is possible to see an interest in the exotic in a more decentered way. I mean, on the one hand, I can refrain from taking a picture, reproaching myself with the thought that it is unethical to perpetuate a stereotype of a primitive backward society. But isn’t there a certain smugness in that posture? I have been struck by the number of people who ask me if I would be in a picture with them, or if they could take my picture. There were, for example, four Sudanese ladies visiting the Syrian National Museum, sponsored by their Ministry of Education. And the charming girls from Aleppo at Qasr Azem in the old city. Ghazi is clearly an object of fascination, what with his sagging pants, Bob Marley shirts and wild streaked ‘fro, and in the poorest sections of Cairo, the attention he gets is not particularly friendly. The ubiquity of American television notwithstanding, we are as exotic to “them” as they are to “us.”

But what did I go out in the desert to see? Something real, something authentic, à la Baudrillard? People who still eat fresh food, still know how to make things, still struggle against an untamed environment? All of that seems exactly true. But there is also the search for origins, the search for evidence of cultural continuity. It is an unspeakable joy to see up close what the Crusaders saw: the Islamic arches which were to revolutionize Christian architecture. Or the Roman columns (of Greek inspiration) stripped from a Crusader castle and now on either side of the mihrab in the mosque. Fragments of silk carried along the silk route from Asia to the Middle East are on display in the National Museum, and in Qasr Azem there are robes and dresses in the same silk brocade patterns now sold in the Souq el Hamidiyeh, where I used to come and buy them with reckless abandon. These silk patterns are woven on a French-designed Jacquard loom, which is not without likeness to early computers.

Next to the 10th-century Al Azhar mosque in old Cairo is a caravanserail, called the Wikala el Ghouri, which was built in 1504. In that setting, last night, Ghazi and I watched a performance of Sufi dancing, known commonly in America as whirling dervishes, and locally and I think not entirely respectfully as “tannura” ("skirt"), since the performers call themselves Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe. The musical instruments were ancient – the rababa, a stringed thing, a kind of flute, and of course the drums. The dancing was beautiful, so artful. The troupe – which looked Turkish to me – was all male, but a middle-aged man mimed the movements of a harem dancer with exquisite grace and irony. It was an unforgettable spectacle, and will probably be the highlight of our Cairo visit.

As I understand it, the whirling dancing induces a mystical trance. VERY plausible. Watching the artful labor of love, I thought about the first time I had ever heard of the great Sufi mystic poet Jalal ed-Din Rumi, who wrote in the 13th century in a region of what is now known as Afghanistan. I was on Brant Avenue near Bailey, driving to what I hoped would be work, on the morning of September 12th, 2001. NPR was rebroadcasting an interview with Coleman Barks, who had translated Rumi's poetry in English. Here is the selection they read, as I pulled the car over to the side of the road, momentarily incapacitated.

Poem 51

Out beyond ideas of wrong-doing and right-doing,

There is a field. I'll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase "each other"

doesn't make any sense.

So in Jordan, as previously mentioned, one frequently sees an image showing the late King Hussein in a warm and friendly pose, sitting with his son and heir King Abdullah. In Syria you see a montage consisting of an image of the late Hafez el-Asad next to an image of his son and heir, Bashar el-Asad. There is sometimes a third face, that of the president's brother -in-law who happens to be the chief of military intelligence, and who was implicated in the assassination of Rafiq Hariri.. Perhaps because Syria was for so long in the Soviet orbit, the tone of the imagery is more severe; there is no grinning; it is not warmth and happiness being conveyed, but rather raw power. Not “Love me, love my son,” as in Jordan, but rather “Remember how I kicked your ass? Well! You ain’t seen nothin yet!” An enormous gilded bust of Hafez el-Asad at the entrance to the military museum in Damascus is particularly communicative.

In Beirut, in contrast, emotions and political impulses are manipulated via the imagery of martyrdom. Given the decades of civil war, each faction has a long roster of fallen heroes, and recent violence has only made the lists longer. What I don’t know, and couldn’t know without a vastly better grasp of local politics, is the precise agenda for which the images are being exploited. It is obvious enough to surmise that the ubiquitous and larger-than-life images of Hariri and Tueni are fronting a campaign to rid Lebanon of Syrian influence. But there is surely more to it than that. I am curious to know whether the Hariri-Tueni support for rebuilding and modernization was offensive to those who considered that traditional values were being swept away in a rush to become a client state of America and the West, or those who thought that the coercive rhetoric about unity foreclosed a full airing of grievances, or those who thought something else altogether.

Apropos only vaguely of all this, there is an interesting commercial running on MBC2, a satellite TV station which plays American movies with Arabic subtitles 24/7 throughout the region. The commercial shows an Arab woman in a modern house wearing a headscarf and modest dress. She wants to serve orange juice, but is struggling, poor dear, what with the oranges rolling everywhere, and having to wield the big knife and the juicer, and OMG, did she just break a nail? She throws up her hands, and behold, a gleaming two-liter jug of made-from-concentrate orange juice appears magically on her counter, ready to be served to guests. Message: our product is compatible with your traditional values of modesty and hospitality, and if you’re ever going to have LIFESTYLE, you don’t have time to make your own orange juice.

Now we’re all for liberating people from back-breaking demeaning tasks all over the world, and no doubt I have pension stocks in Nestle or whatever multinational is pimping its juice to folks over here. But speaking as someone raised on the miracle of canned food in the 50s, I remember what a revelation it was to taste fresh asparagus, green beans, and chow mein.

Which brings me to the question of what it is that we’re looking for when we come over here. I come to this question via the ethical issue of photography here, where every published image of an exoticized other reinforces stereotypes of Arab backwardness and by implication the natural right of the superior civilization to help itself to local resources. On the other hand, if we suspend consciousness of the staggering economic imbalance separating our worlds, it is possible to see an interest in the exotic in a more decentered way. I mean, on the one hand, I can refrain from taking a picture, reproaching myself with the thought that it is unethical to perpetuate a stereotype of a primitive backward society. But isn’t there a certain smugness in that posture? I have been struck by the number of people who ask me if I would be in a picture with them, or if they could take my picture. There were, for example, four Sudanese ladies visiting the Syrian National Museum, sponsored by their Ministry of Education. And the charming girls from Aleppo at Qasr Azem in the old city. Ghazi is clearly an object of fascination, what with his sagging pants, Bob Marley shirts and wild streaked ‘fro, and in the poorest sections of Cairo, the attention he gets is not particularly friendly. The ubiquity of American television notwithstanding, we are as exotic to “them” as they are to “us.”

But what did I go out in the desert to see? Something real, something authentic, à la Baudrillard? People who still eat fresh food, still know how to make things, still struggle against an untamed environment? All of that seems exactly true. But there is also the search for origins, the search for evidence of cultural continuity. It is an unspeakable joy to see up close what the Crusaders saw: the Islamic arches which were to revolutionize Christian architecture. Or the Roman columns (of Greek inspiration) stripped from a Crusader castle and now on either side of the mihrab in the mosque. Fragments of silk carried along the silk route from Asia to the Middle East are on display in the National Museum, and in Qasr Azem there are robes and dresses in the same silk brocade patterns now sold in the Souq el Hamidiyeh, where I used to come and buy them with reckless abandon. These silk patterns are woven on a French-designed Jacquard loom, which is not without likeness to early computers.

Next to the 10th-century Al Azhar mosque in old Cairo is a caravanserail, called the Wikala el Ghouri, which was built in 1504. In that setting, last night, Ghazi and I watched a performance of Sufi dancing, known commonly in America as whirling dervishes, and locally and I think not entirely respectfully as “tannura” ("skirt"), since the performers call themselves Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe. The musical instruments were ancient – the rababa, a stringed thing, a kind of flute, and of course the drums. The dancing was beautiful, so artful. The troupe – which looked Turkish to me – was all male, but a middle-aged man mimed the movements of a harem dancer with exquisite grace and irony. It was an unforgettable spectacle, and will probably be the highlight of our Cairo visit.

As I understand it, the whirling dancing induces a mystical trance. VERY plausible. Watching the artful labor of love, I thought about the first time I had ever heard of the great Sufi mystic poet Jalal ed-Din Rumi, who wrote in the 13th century in a region of what is now known as Afghanistan. I was on Brant Avenue near Bailey, driving to what I hoped would be work, on the morning of September 12th, 2001. NPR was rebroadcasting an interview with Coleman Barks, who had translated Rumi's poetry in English. Here is the selection they read, as I pulled the car over to the side of the road, momentarily incapacitated.

Poem 51

Out beyond ideas of wrong-doing and right-doing,

There is a field. I'll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase "each other"

doesn't make any sense.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home