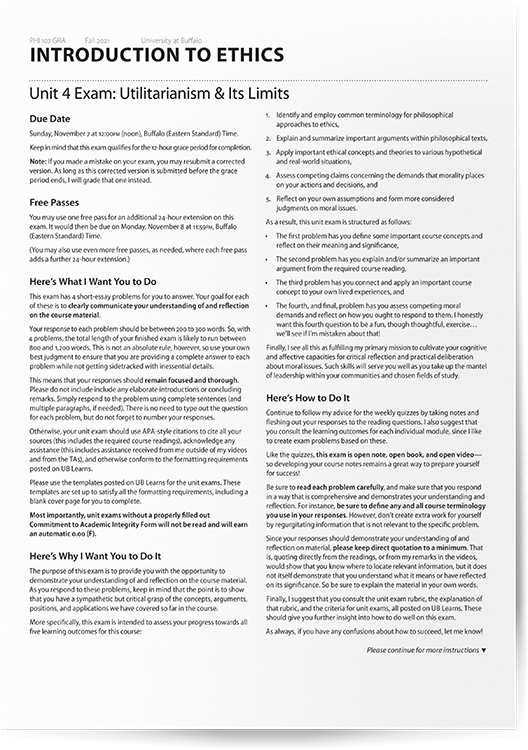

Unit 4: Utilitarianism & Its Limits

Photo: Colleen Hayes / NBC.

Not everyone is satisfied with John Stuart Mill’s Utilitarian justification of rights. Philosophers like Robert Nozick suggest that rights possess an intrinsic moral value that is independent of whether rights may (or may not) promote the utilities associated with security. Such philosophers adopt an alternative approach to morality, known as Deontology, which imposes firm constraints on our actions. At the very least, say most Deontologists, there should be a constraint against harm, and it is that constraint that we will examine in this module.

To that end, we have five learning outcomes. When you finish this module, you will be able to…

- Describe how constraints are supposed to offer an alternative to Utilitarianism,

- Distinguish between Teleological and Deontological ethical theories,

- Summarize Robert Nozick’s justification for a constraint against harm,

- Critique the common distinction between doing and allowing harm, and

- Assess whether a constraint against intending harm actually makes moral sense.

Read This:

|

Harry Truman and Elizabeth Anscombe

|

Moral Constraints and the State

|

Context

Recall that John Stuart Mill sees rights as instrumentally valuable. That is, rights may not have value in and of themselves, but they remain highly effective means for protecting our ability to cultivate and exercise our higher-order capacities. So rights, in their special way, typically promote the greater good. A similar argument could be made other common moral rules, like “don't lie”, “don't steal”, and so on.

Even so, the merely instrumental value of rights and other moral rules still suggests that they may occasionally be violated in the name of the greater good. For instance, James Rachels and Stuart Rachels discuss the example of using atomic weapons in World War II, which may have promoted the greater good—even though it violated moral rules against harming civilians during wartime.

Rachels and Rachels note that this decision angered the British philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe (1919–2001), who thought that certain moral rules (like those associated with human rights) ought never to be broken, no matter what.

Robert Nozick (recall that we read his “Experience Machine” back in Module 17) agrees with Anscombe: rights do have intrinsic value. That is, Nozick argues that it is never morally acceptable to violate rights, even if doing so may promote the greater good. Understood this way, rights place firm (maybe even absolute) constraints and limits on what a person may or may not do. So, for example, if using atomic weapons violates a civilian’s right to life, it is simply not morally permissible to use them.

In this reading, Mill directly responds to such concerns by attempting to resolve apparent tensions between utilitarianism and justice, showing how utilitarianism still supports our commonsense notions of justice. Following that, the section from James Rachels and Stuart Rachels provides additional responses that utilitarians might make to their critics.

Reading Questions

As you read, keep these questions in mind:

- How do James Rachels and Stuart Rachels use Harry Truman’s decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan to illustrate how there might be some absolute moral rules that should never be violated?

- What is Robert Nozick’s distinction between a “utilitarianism of rights” (1974, p. 28) and a theory that “places [rights] as side constraints upon the actions to be done” (1974, p. 29)?

- What does Nozick mean by the “inviolability of other persons” (1974, p. 32), and what reasons does he give to justify the importance of this idea and to then claim that constraints express this inviolability?

- What are “libertarian constraints” (1974, p. 33)? Why does Nozick believe that if the “form” of morality involves constraints, then the “content” of morality must have libertarian constraints as well (1974, p. 34)?

- In the last section, Nozick wants to identify the set of special characteristics that a person must have in order for moral constraints to apply to how others may treat that person. Put differently: the idea is that if you possess these characteristics, then you are due “respect” from everyone else. And if we truly respect you, then we must accept constraints (or limits) on how we may treat you. What characteristics does Nozick consider, and which ones does he ultimately seem to suggest are essential for there being constraints on how we may treat a person?

Although I strongly suggest that you write out brief answers to these questions, you do not have to turn in written responses. You do, however, need to be prepared to answer questions like these on module quizzes and the unit exams.

References

Rachels, J., & Rachels, S. (2018). Harry Truman and Elizabeth Anscombe. In The elements of moral philosophy (9th ed., pp. 133–135). McGraw-Hill.

Nozick, R. (1974). Moral constraints and the state. In Anarchy, state, and utopia (pp. 26–53). Blackwell.

Watch This:

|

Video 1

|

Video 2

|

|

Video 3

|

Video 4

|

|

Video 5

|

Do This:

|

Module 21 Quiz

Due: November 6 |

|

|

5 Tweets this Week

Due: November 6 |

|

|

Unit 4 Exam

Due: November 7 |

|

Submit the Unit 4 Exam here! |