Unit 2: On What is Morality Grounded?

Photo: Colleen Hayes / NBC.

With so many disagreements between different people about what is right and what is wrong, it is tempting to say that there are no right answers to ethical and moral issues. Perhaps morality is simply relative to our own society and culture? In this module, we analyze and evaluate that popular idea, which is known as Cultural Relativism.

To focus our analysis, we have four learning outcomes. By the end of this module, you will be able to…

- Explain the idea of Moral Relativism and how Cultural Relativism is one version of it,

- Recognize the nature and appeal of Cultural Relativism,

- Assess the anthropological arguments justifying Cultural Relativism, and

- Summarize a reductio ad absurdum argument against Cultural Relativism.

Read This:

|

Anthropology and the Abnormal

|

The Challenge of Cultural Relativism

|

Context

Moral Relativism is the position denying that there are objective and universal moral values, norms, and principles that apply to all people everywhere. Instead, ethical relativism affirms that whether it is morally right or wrong for a person to act in a certain way depends on (“is relative to”) either cultural or individual acceptance.

As a result, there are two different versions of Moral Relativism:

- Cultural Relativism, which argues that morality is a matter of social/cultural acceptance because morality is solely determined by the customs and laws of one’s society/culture, and

- Ethical Subjectivism, which argues that morality is a matter of individual acceptance because morality is solely determined by one’s own personal reactions or feelings.

In the first reading, Ruth Benedict (1887–1948) presents observations from her anthropological research on the customs and behaviors of indigenous North American peoples. From these observations, she concludes that Cultural Relativism is obviously correct.

Meanwhile, James Rachels and Stuart Rachels are not convinced. They analyzes the structure of Benedict’s argument, claiming that it goes well beyond what the anthropological facts or arguments can establish.

(As for Ethical Subjectivism? We will cover that in the next module.)

Reading Questions

As you read, keep these questions in mind:

- Ruth Benedict claims that “morality differs in every society, and is a convenient term for socially approved habits” (1934, p. 73). How does Benedict justify this claim of Cultural Relativism?

- According to Benedict, why can’t I (as an American) criticize the bereavement traditions of the Kwakiutl peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast?

- If Benedict is correct, how does justification in ethics work? In other words, according to Cultural Relativism, what is the “right” way for getting others to agree with you concerning what is morally right and what is morally wrong?

- Benedict’s argument might be considered a form of the Cultural Differences Argument. Why do James Rachels and Stuart Rachels claim the Cultural Differences Argument is unsound?

- What unsettling consequences of Cultural Relativism do Rachels and Rachels identify?

Although I strongly suggest that you write out brief answers to these questions, you do not have to turn in written responses. You do, however, need to be prepared to answer questions like these on module quizzes and the unit exams.

References

Benedict, R. (1934). Anthropology and the abnormal. Journal of General Psychology, 10(1), 59–82.

Rachels, J., & Rachels, S. (2018). The challenge of cultural relativism. In The elements of moral philosophy (9th ed., pp. 14–32). McGraw-Hill.

Watch This:

|

Video 1

|

Video 2

|

|

Video 3

|

Video 4

|

|

Video 5

|

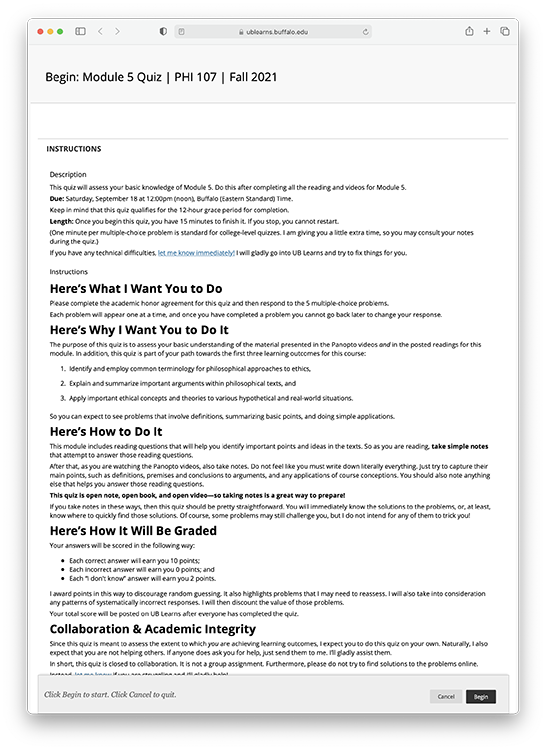

Do This:

|

Module 5 Quiz

Due: September 18 |

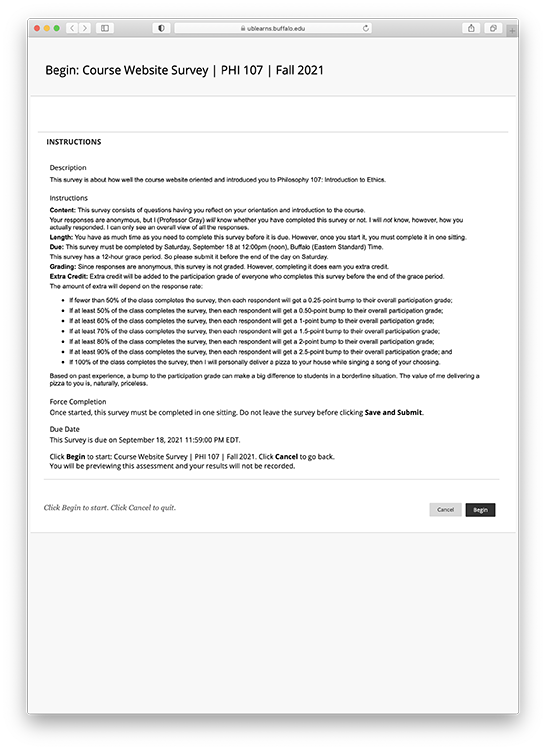

Course Website Survey

Due: September 18 |

|

5 Tweets this Week

Due: September 18 |