Toponyms, Critical Cartography, and Maps -- Judith Goldman class

Student map research

- Cross-section Kowloon Walled City: what was the densest place on Earth. Different kind of mapping. See large version of the map.

- 7 Maps That Show Where Bad Stuff Happens

- 10 Hoax Definitions, Paper Towns, and Other Things That Don’t Exist. Scroll down to “Agloe, NY” entry

- Smell and the City. Blog about New York City smells, with mapping.

- Map of Narnia.

- Psychogeography- the study of how geographic environment inflences psychological state. It is fascinating how relatively abstract concepts such as emotions and arousal can be mapped on to a concrete physical space. How is the data collected in a legitimate manner? How do we make the connection between a person's internal and external states? Are such maps more artistic than scientific?

- Emotion Maps. Printed maps showing cities by emotional states.

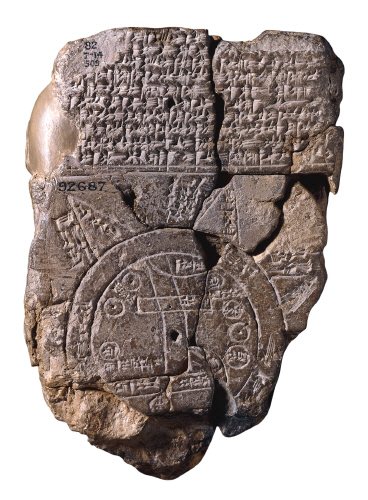

| 1. "Mountain" (Akkadian: šá-du-ú) 2. "City" (Akkadian: uru) 3. Urartu (Akkadian: ú-ra-áš-tu) 4. Assyria (Akkadian: kuraš+šurki) 5. Der (Akkadian: dēr) 6. ? 7. Swamp (Akkadian: ap-pa-ru) 8. Elam (Akkadian: šuša) 9. Canal (Akkadian: bit-qu) 10. Bit Yakin (Akkadian: bῑt-ia-᾿-ki-nu) |

11. "City" (Akkadian: uru) 12. Habban (Akkadian: ha-ab-ban) 13. Babylon (Akkadian: tin.tirki), divided by Euphrates 14 — 17. Ocean (salt water, Akkadian: idmar-ra-tum) 18 — 22. Mythological objects |

Anaximander Ἀναξίμανδρος Anaximandros; c. 610 – c. 546 BC

Anaximander Ἀναξίμανδρος Anaximandros; c. 610 – c. 546 BC

World's oldest map: Spanish cave has landscape from 14,000 years ago (Telegraph article 2009); image.

TOPONYMY

On Christian Jacob:

"naming is a mode of symbolic appropriation that provides virgin territories with a memory, a grid that dispossess space of its otherness and turns it into an object of discourse, subject to the constraints of linguistic reference, that seeks to make every identifiable place correspond to a name"

Here Jacob is talking about the fundamental, ultimate motivation that inspires place-names. It makes what is foreign, unchartered territory a part of "our world" (world being more than just the planet we inhabit) and reflects a universal human trait--the desire to demystify and possess. The first step of this is simply assigning a name to the subject so that it can be talked about and purged of its otherness. It is difficult to imagine any truly "virgin" territories on planet earth in the 21st century, that haven't been mapped in some way or another (e.g., satellite imagery) but a good example of this would be the territories of outer space. Though the majority of the population has not visited, let alone properly and directly observed what lies beyond the atmosphere, the mere act of naming the planets in the solar system (and as a result subjecting them to discussion in classrooms and elsewhere) people all over the world share the common feeling of possession. The feeling that despite its great distance, outer space is, in a very significant sense, a part of our world. That may be why we feel comfortable referring to the immediate cosmos as "OUR solar system."

Discussion of Stewart, Names on the Land (names in Buffalo)

What Stewart said about how the names of places changed as they were moved between languages made me think about where I grew up, South Salem, NY. According to a tour guide we had on a third grade field trip, it’s one of the oldest settlements on North America. Walking through the woods it’s common to find Native American meeting stones, unmarked graves from the 18th century (creepy), and farm tools from the 19th century. Thinking about what Stewart said about how old places like this came to be named, I looked at the roads, lakes, and rivers and noticed something interesting. The names of most things/places surrounding where I live are a mixture of (what I assume to be) Native American names and English names. For example, My house sits on the corner of Kitchawan and Mill River Road. Strangely, Kitchawan Road is the only road in the town that has a Native American name however, and I presume it’s because it leads to Lake Kitchawan half a mile down the road from where I live. The rest of the roads have English names (Smith Ridge Road, Old Church Lane, Grandview Road, etc.) and lead to boring places like Pound Ridge or Cross River. For some reason all of the bodies of water (rivers, lakes, and ponds) as well as land reservations (parks, preserves, etc.) have been given Native American names. Names like Lake Rippowam, Lake Waccabuc, and Mamanasco Lake. Nobody in my community, or at least nobody that I know, knows why we adopted this naming scheme. I assume it’s because the names for “static” things, like the rivers and lakes, were there before everything else. Another weird thing about the naming of places is that all of the locations named after people with English sounding names like Smith, Jay, or Levy are actually named after Native Americans that either adopted or were given English names.

Notes from a previous class, 2013.

19 October 2017

http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~dbertuca/maps/goldman.html