Margaret and Michael Hussey live in Surrey, in the UK. In this essay, Margaret eloquently describes Michael's reactions to her efforts as well as those of his clinician Nicki, as they work together to help Michael regain some of his ability to communicate, following his stroke. Especially significant are Margaret's descriptions of how Michael assumes his own responsibility for improving his speech, memory, and writing.

THERAPY

Nicky, the speech therapist, comes into our lives and, as the early spring bulbs start to flower and the winter cold decreases, her weekly visits give our lives a focus and I feel a cautious optimism. She is relaxed, encouraging and very ready to praise. When he has difficulty her sympathetic laugh helps him to smile also, and she is quick to notice when he is tired. Michael loves her and wants to give her bottles of wine every time she comes. He is highly motivated to try and perfect any ‘homework’ she has given him before her next visit so a routine develops of doing some practice together every morning after he has got up. Our days gain a sense of purpose and pattern.

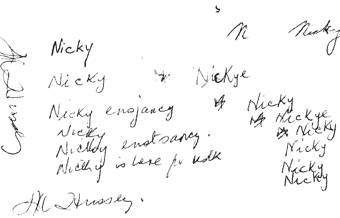

In France, Michael had chosen an A4 sized, spiral bound exercise book for writing and before Nicky’s first visit he practices her name. Most writing attempts at this stage are accompanied by his signature as he knows that he has got that right. ‘Wolk’ instead of ‘work’ is a mistake he still makes but I cannot decipher ‘enstancy’.

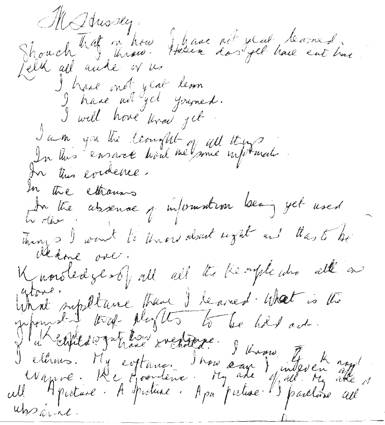

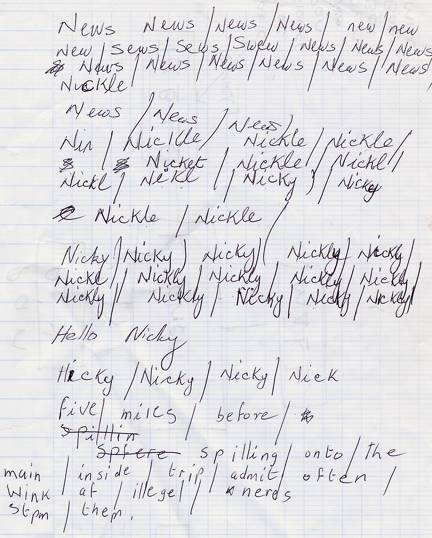

I write a few other words related to what we are doing, such as ‘film’ and ‘news’ and he copies these in careful columns. His inability to read or write is obviously more distressing to him than the inability to verbally communicate. He then writes freely for a page.

That on how I have not yeat learned.

Shouch I know. Hasic does yet have eat here

Lelk all aude or us.

I have not yeat learn

I have not yet yourned

I will have know yet

I am you the leought of all things

In this ensarce woul me some informati

In this evidence.

In the ethausis.

In the absence of information being yet used to other.

Things I won’t to throw about right and thas to be dedone over.

Knowledge of all the keouple who all one above.

What supestance there I learned. What is the information that alights to be hold over.

I a child I have a cholld. I know.

I ethnus. My eojtanc. I how van I in even evanue. My ade of all My ade cell. A

Picture. A picture. A pa picture. I paicture all whs aime.

‘I will have know yet’ is a yearning cry which fills me with pain. Some phrases are like torn fragments of past staff meetings and ‘I am you the leought of all things’ has a Biblical cadence. I do not understand. Is the meaning clear in his own head? His mind appears to be ‘an isle full of noises’ in which shadowy shapes of words fade in and out. One morning in bed he stretches up a hand as if to grasp something. “It..” He mimes being dazzled by a light. “Then..” he mimes being crestfallen and shows that there is nothing in his hand.

Another page is devoted to dogged practice.

The way he veers away from the correct sound of the word is exactly what happens when I try to teach him a word aurally.

“Say ‘knife’.”

“Li..”

“Nnnn.”

“Li..”

“Nnnn.”

“Mmmmm.”

“Look at my tongue.” I wave it round, put it behind my teeth and repeat,”Nnnn.”

“Nnnnnmmmmm.”

“Almost!. Nnni..”

“Ni.”

“Well done! Now ‘knife.’ I elongate the n and the f sound.

“Life.’

“Almost! Knnnnnife.”

“Knnnni. Mmi. Li. Fi.” He shakes his head with exhaustion.

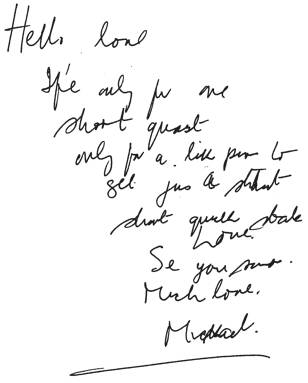

One morning, I leave him sleeping and am out for an hour. When I come back he is not in the house. I am terrified then find a note on the kitchen bench.

Hello love

If’e only for one

short quast

only for a lik pm to

get just a shant

short quick sbale.

Love

Se you suo.

Much love

Mickael

Cold panic. I run to the lakeside and look around. No sign of him. I ring Val because I can’t bear the silence and to put a stop to my imagination. She agrees that all I can do, for the moment, is wait. Twenty minutes later he walks back in, a little puffed but apparently fine. I act a warmly casual role.

“Have you had a lovely walk?”

“I…” He embarks on a mime.

“Did you get lost?”

He nods and mimes walking round and round and looking for the right path. It is two years later before he is able to explain that he had walked to the bank in Woking and had somehow managed to convey to the teller that he wished to have £400 in cash. He had then walked around to the Halifax and paid it into our mortgage account as he was worried that I might not think about it. While trying to take a short cut on the way home he found himself in streets he did not know and just kept walking until he found something familiar.

Nicky, initially, homes in on his desire to read and writes the name of a room in the house, such as the kitchen, followed by a list of words from which he must choose and write the items which should go in the kitchen. He has sheets of pictures of single objects with which he must match a written name. He practises reading and writing these words with the seriousness formerly devoted to educational policies and guidelines.

Pean/ Pan/ Pan/Bean/Table/Table/Table/kitchen/kitchen/Kitchen/oven/oven/Table/Table/Kitchen/oven/oven/mikh/Table/Tenely/Tenely/Table/Tree/Treer/Tree/Flower./Pan/over/Bed/Bed/Bath/Barth

Toiler/Toiler/Toiler/mirrour/mirrou/Bathroom/Bathroom/Bathroom/sink/sink/Bath/Bath/

Bath/Tolet/Toler/Toter/Watch/Watch/water/watch/match/sink/sink/sink/fridak/fridge/fridpee/fridae/bath/Bath/tree/Tree/Tree/mirror/mirror/mirrer/mirrek

Comb/comb/write/write/write/copy/copy/driw/driw/driw/wriw/Pinture/pirturlel/camb/camb/camb/cumb

He prints the words very deliberately and the style of writing has not changed. I find it deeply touching to watch him put his finger on a word and say it, over and over again and it is satisfying to find that I have a necessary role in this process of learning. On his own, he would never remember the sounds of the words used in Nicky’s session and, each day, we have to go over and over the names she has introduced. Words that he said easily yesterday are difficult today. All I can offer him is my experience from years of playing the piano: if you cannot get it right, practice it again. His face contorts with the effort and the journey from the beginning to the end of a word can be painfully long.

“Room.”

“Mmmm..”

“Rrr…”

“Tuh..”

“Rrrrr…”

“Tuh…no…let me…Duh..”

“Rrrr..”

“Aaar..”

“Yes! Rrrrrrrr…..”

“Aaarr…..”

“Roo…”

“Roa..”

“Put your lips like this.” I purse my lips in a little circle. “Pretend you’re going to give me a kiss.”

He finds it so hard to look at what my lips are doing and to translate it into action.

“Roh..ow..oh..”

He starts to giggle and soon we are both laughing helplessly. Our shared mirth marks a return to intimacy. I kiss him saying “Mmmmmmm.” When we have sobered up he suddenly finds it.

“Room! Room!” But when I ask him to put a book in theroom where we are going to sit he doesn’t know what I mean until I point to the sitting room. The connection between the words he is so anxious to be able to read and their meaning seems very tenuous.

His spontaneous speech is, from time to time, throwing up new words and I am thrilled when each one arrives but completely puzzled at his inability to repeat that same word deliberately.

“Some wine?” he asks suddenly, one evening.

“Bravo! You’ve just said ‘wine’!”

He looks completely uncomprehending.

“Wine,” I repeat. “Wine.”

He shakes his head and cannot say it again.

The relentless practise of single words without a context starts to feel arid. One evening, when we are both tired and there is nothing worth watching on the television I rummage in a box of tapes that a friend has lent us. I have not tried them before this as I did not think Michael would be able to follow the meaning from the spoken voice only. I put on a recording of T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ and Michael’s face is rapturous. The words reach through and feed him. He has often taught the poems and knows them well so the meaning vibrates deeply for him without the need to follow every word.

Nicky writes a grid of letters for him to practise.

P P P P P

B B B B B

P B P B P

t t t t t

d d d d d

t d t d t

k g k g k

She talks to him of front sounds, middle sounds and sounds at the back of his mouth, trying to cross the barrier he has about making sounds deliberately. When we practise he pants with the effort and, after half an hour, can go to bed and be asleep in minutes. He does not understand ‘front,’ ‘middle’ and ‘back.’ I resort to cruder methods. For ‘g’ I put my finger down his throat to touch the place where the sound is made. I put my lips on his and we do a gentle ‘p’ then an explosive ‘b.’ We spend ages looking in the mirror at what our mouths are doing when we make a sound. I say ‘look’ and make the sound but his eyes have flickered away at the relevant moment. All the will power is there to learn but his attention span is very short. At the end of a week of intensive practice he can look at each letter singly and, with some false starts, manage to say it but saying ‘p’ and ‘b’, ‘t’ and ‘d’ or ‘k’ and ‘g’ consecutively is just too hard.

I search in the public library for a children’s book that he might be able to tackle and find a little book for teachers to read to very young children on ‘Bullying.’ Michael had been involved in a European Union initiative of producing materials for teachers to use when dealing with this problem. Perhaps his interest in the subject will help him to accept a book obviously destined for children.

It is such hard work. It is so difficult for him to say the word ‘bully’ which, at best, comes out as ‘Bowllllahee’ and it takes us over an hour to work our way down one page containing a dozen words. I am astounded by his desire to master the task and excited as his progress is evident. He copies some sentences into his writing book, still carefully printing the words rather than using handwriting. ‘When my sister takes my toys and breaks them, I feel bullied.’ He then practises individual words, often with slight mispronunciation, and he looks puzzled until, suddenly, the right sound comes and, like a string player or a singer finding the centre of the note, he usually recognises when it is right. ‘Susster. Susster. Susster? Saster…soss…susst…si..sister..yes, sister.’ Sometimes I intervene and say it for him, but that is often not the right thing to do when he is almost there. ‘Ssh..let me.’ My intervention can ruin his concentration and he loses the word. At other times he cannot get it, with or without my help and, sometimes, his face crumples and the tears pour down his cheeks. I cry with him. I tell him how brave I think he is and what progress he is making. I repeat the praise Nicky has given him and how our close friends see differences every time they see him. It is no use. “Stupid,” he sobs. “Uss…ussse..lo... Useless. Less. Less.” He lashes himself with each syllable. These are both new words, but not words I want to hear. I hold him until he is quiet and, on one occasion, venture a little further than just giving comfort. I do not want to fracture the fragile confidence that is developing but I suspect that he is battling with his expectation that language might return very quickly. “Michael, no one says it is going to be easy.” I rub the side of his head. “The stroke has taken away your language. But you have a clever brain and it can relearn language. It is very hard work.” I know he is hearing the gist of what I am trying to say. “You know what it is like for things to be tough. When you were a child at Driefontein life was hard.” I can feel his body react to the word ‘Driefontein’ and he looks up into my face. “But you knew that education was the way forward and you worked to make your life better. Now life’s tough again. But you will win. You are winning just as you did before. Don’t give up now.”