George Dalgarno

1628-1687

George Dalgarno was a 17th century Scottish intellectual and teacher. He published two influential books, one in 1661, on a universal language (Ars Signorum—the Art of Signs) and the second, in 1680, on methods for teaching the deaf (Didascalocophus: Or, the deaf and dumb man’s tutor). He started a school in Oxford, UK, where he served for many years as headmaster.

George Dalgarno was a 17th century Scottish intellectual and teacher. He published two influential books, one in 1661, on a universal language (Ars Signorum—the Art of Signs) and the second, in 1680, on methods for teaching the deaf (Didascalocophus: Or, the deaf and dumb man’s tutor). He started a school in Oxford, UK, where he served for many years as headmaster.

Dalgarno advocated writing as a natural method for teaching the deaf, believing that written language for the deaf could be developed as is language for children with normal hearing. He placed great emphasis on early intervention, advocated finger spelling of words in space, through the use of a glove with letters inscribed on it. He felt that his manual alphabet be made available and taught to all children in schools.

A table of contents of Didascalocophus:

The introduction with a key to the following discourse: In this first section of his short book, Dalgarno offers a schema for how information is learned and communication takes place. He describes the roles of the different senses in relation to the Soul. He provides definitions of terminology for use in the following sections.

Chapter 1: A deaf man as capable of understanding the expressing a language, as a blind. Here Delgarno argues that sight and hearing are equally valid ways to convey arbitrary symbols of language. He makes his argument for their equal role by comparing language learning and communication of the deaf man with the blind man.

Chapter 2: A deaf man capable of as early instruction in a language as a blind. “Taking it for granted, That Deaf people are equal, in the faculties of apprehension, and memory, not only to the Blind; but even to those that have all their senses: and having formerly shewn; that these faculties can as easily receive of Sounds thro the Ear: It will follow, That the Deaf man is, not only as capable; but also, as soon capable of Instruction in Letters, as the blind man” (From Delgarno, p. 302 in Cram & Maat, 2001). In this chapter Delgarno argues for the caregiver to talk to the deaf child in the cradle using fingerspelling. He promotes and argues for the usefulness of his letter glove as a mode of communication. The method he advocates is naming (spelling words and associating them with objects).

Chapter 3: Of a deaf mans capacity to speak. Delgarno continues comparing abilities and disabilities of deaf with blind and recommends that speech be taught to the deaf through touch and writing. He does not claim the speech will be perfect, but it will be understandable.

Chapter 4: Of a deaf man’s capacity to understand the speech of others. Delgarno says that a deaf man will not be able to distinguish all the sounds of the language just by watching the mouths of others. He needs to read the context and to guess, and would benefit from fingerspelling.

Chapter 5: Of the most effectual way to fill a deaf mans capacity. Here Delgarno gives some hints for educating deaf children—with diligence (practice) being the most important tactic:

General principle: Fill his head as full of the imagery of the world of words of mans making, as it is of the things of this visible world created by Almighty God (p. 314)

- Use the pen and the fingers much (p. 316)

- Have tablets in several convenient places around the room

- Have common forms written on the tablets (e.g., common sayings)

- Use pocket table books

- Practice the alphabet on the fingers—using this to communicate

- Keep the scholar from signing in other ways, focusing only on the letters.

- Match the abilities of the scholar and teacher (slow scholar, slow master)—“One Dunce to teach another” (p. 317).

Chapter 6: of a deaf mans dictionary. In chapter 6, Dalgarno reflects on what sort of language is easiest to learn. He answers—a universal language of real characters, such as one he developed several years earlier. He also says the language from where the student lives and of the people who he around him will be easiest for the deaf student to learn. He says teach grammar after sounds and words are learned. His language teaching starts with the letter, proceeds to the names of familiar and concrete things (concrete substantives) and then covers the more abstract and less familiar vocabulary items. Use the almanack and watch to teach time. The good teacher needs to follow the pupil’s capacity.

Chapter 7: Of a grammar for deaf persons. In chapter 7 Delgarno describes various issues of morphology and syntax. He recommends teaching these by rule, allowing the student to deduce the rule himself. Delgarno observes that while morphology is traditionally subdivided into agreement and government, following Latin principles, this division is not appropriate for English.

Chapter 8: Of an alphabet upon the fingers. In this final chapter, Dalgarno describes his system for finger spelling. He proposes a layout of where the letters are associated with different spots on one hand, and tells how vowels and consonant clusters can be designated through pointing.

- Place the letter-glove or imagined letters on the right hand.

- Touch the places of the vowels with a cross touch with any finger of the right hand.

- Point to the consonants with the thumb on the right hand.

- Abbreviate double and triple consonants.

Delgardo sees his manual alphabet being of use to everyone—for example, people can use it to communicate silently with one another in the dark.

Writings by George Dalgarno

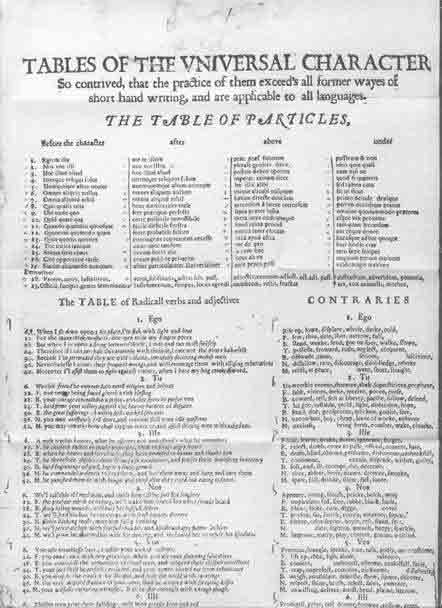

Dalgarno, Geroge (1661). Ars Signorum or a universal character and philosophical language. By means of which speakers of the most diverse languages will in the space of two weeks be able to communicate to each other all the notions of the mind (in everyday matters), whether in writing or in speech, no less intelligibly than in their own mother tongues. Furthermore, by this means also the young will be able to imbibe the principles of philosophy and the true practice of logic far more quickly and easily than from the common writings of philosophers. (Commonly referred to as: The art of signs). London: J. Hayes. . Reprinted in David Cram & Jaap Maat (eds.) (2001). George Dalgarno on universal language: The Art of Signs (1661), the deaf and dumb man’s tutor (1680), and the unpublished papers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dalgarno, George (1680). Didascalocophus or the deaf and dumb mans tutor, to which is added a discourse of the nature and number of double consonants: both which tracts being the first (for what the author knows) that have been published on either of the subjects. Oxford: Theater in Oxford. Reprinted in David Cram & Jaap Maat (eds.) (2001). George Dalgarno on universal language: The Art of Signs (1661), the deaf and dumb man’s tutor (1680), and the unpublished papers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.