My Grandpa Lee

by

Tina Bennett-Kastor

July 24, 2002

In

a sod house on the wind-blown prairie of western Nebraska, Lee Edward Travis

was born, the second child of Mary Eunice Speer Travis and her husband Charles

Edward. Mary was not quite 21 years old, and Charles, who had been her teacher,

was thirty. Fifteen months earlier, at age 19, Mary had borne her first child,

Ralph. Now, on that June day, it was as if Ralph had acquired a twin, for

there would not be another Travis for three years. So Ralph and Lee grew up

side by side, playing, doing chores around the farm, and eventually going

off to school together.

In

a sod house on the wind-blown prairie of western Nebraska, Lee Edward Travis

was born, the second child of Mary Eunice Speer Travis and her husband Charles

Edward. Mary was not quite 21 years old, and Charles, who had been her teacher,

was thirty. Fifteen months earlier, at age 19, Mary had borne her first child,

Ralph. Now, on that June day, it was as if Ralph had acquired a twin, for

there would not be another Travis for three years. So Ralph and Lee grew up

side by side, playing, doing chores around the farm, and eventually going

off to school together.

An extraordinarily brilliant young man in a family of brilliant minds, Lee’s childhood had been shaped by the earthy realities of farm life on the plains and tempered by the Mormon faith of his family. These two influences were to make of him a man rigidly committed to the validity of the empirical, to truths that could be seen, heard, felt, and measured, and yet also a man fervently trying to understand the most intangible of human behaviors. In attempting to measure what defied measurement, he very nearly lost his own intangible soul, and did indeed for a long time lose the faith which had led him as a youngster to be baptized in the cold waters of a Nebraska creek Late in his life, he was finally able to reconcile the scientist with the philosopher.

As the family grew, Charles Travis eventually moved them from the little sod structure to a large frame house. At certain times of the year, hired hands added to the increasing population of the farm, and Mary Travis worked tirelessly to run the household, feed the workers, and keep her family clothed while Charles moved back and forth between the farm and his position as Superintendent of Schools in Imperial County. All the while, more babies came. Lee once related how his mother was in labor with one of the children when she was preparing a meal for the farm workers. As she carried a huge vat of boiled apples from the stove, the baby began to crown, and she hastily set the vat down, went into another room, and delivered herself of the infant. Afterwards, she got herself cleaned up and served the lunch while Charles asked Lee to dig a hole outside and bury the placenta.

At age fifteen, Lee left the farm, along with Ralph, to attend Graceland College in Lamoni, Iowa. His parents had several more children. One little boy lived only a couple of weeks, and Charles wrote to his sons in Iowa to report that “little Albert came and went.” The Travis family was so wide-ranging—there were 25 years between the eldest and youngest offspring--that the thirteenth and last child, Mary Amy, was born just two months before her nephew Paul, Lee’s oldest child.

At Lamoni College, the boys were stellar students if not stellar citizens. The president of the college sent Charles a testy letter complaining that Ralph and Lee had stolen prairie chickens from the laboratory farm, had cleaned and roasted them, and had eaten them for dinner. He insisted on remuneration. Charles replied with a note instructing the president to use the enclosed money to feed his boys more adequately so that hunger would not force them to steal.

Lee and Ralph were handsome, tall, and strong young men. They may have been at a Mormon college, but they were also teenagers with surging hormones. Lee had arranged for a tryst in the nearby woods with a young woman of the college, and in order to make the experience more comfortable he decided he would toss his mattress out the window, jump out onto the mattress, and then carry it to the specified site. Unfortunately, the president was strolling past the dormitory at the moment the mattress landed. We can only imagine the conversation that ensued.

Such moral lapses as stealing chickens and engaging in premarital amorous adventures were perhaps a symptom of Lee’s waning religious faith. By the time he finished Graceland College and moved on the University of Iowa, Lee had walked away from everything he had learned about God or anything the Book of Mormon might have offered. As a graduate student, he was a thoroughgoing atheist, and threw his fate in with logical positivism. Science was to be his god. He had been hand-selected by the dean of the medical college to be the trailblazer of a brand new discipline, one that had not yet been given a name. He was to study brain anatomy, physiology, speech, acoustics, and the still nascent subject matter of psychology. His particular fascination with human speech eventually focused on the phenomenon of stuttering. This problem he attacked with energy, creativity, and all the intensity his 196-point I.Q. could muster.

Yet even in his quest for the measurable, physical characteristics of language, the intangible and the ineffable continued to haunt Lee Edward Travis. Having been analyzed by a psychotherapist who was himself analyzed by Freud, Lee was trained to search for underlying, non-physiological explanations of physiologically manifested problems. Here he encountered a paradox: language was a non-physical, almost spiritual quality of man that presented itself in the physicality of speech. Still, there must be an underlying, physiological explanation for language, an empirical reality upon which the hat of language was hung. At the same time, he searched for a psychological, almost spiritual defect that he believed might underlie the physiological phenomenon of inarticulate speech. He was working two ways at once, backwards and forwards, from notions of cerebral dysfunction and short-circuits in the neuro-muscular apparatus to the concept that, as one of his book titles reveals, stuttering was a manifestation of “the unspeakable feelings of people.”

Lee earned his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees in three consecutive years. He won a Fulbright to Amsterdam where he was trained in the new technology of electro-encephalography. Back home in Iowa, he became one of four researchers racing to be the first in the United States to record brain waves. He enlisted the help of his younger brother Leslie, an engineer, to build an EEG device. He recorded brain waves voraciously, those of animals and humans, stutterers and non-stutterers, under stress and without stress. He recorded his own brain waves while speaking, resting, and once even during a 2-week attack of hiccoughs. Electrodes had to be attached subcutaneously in those days, and it was painful to reinsert them daily. Lee took to getting up from his EEG measurement and walking straight into the lecture hall to teach, electrodes attached, occasional drops of dried blood still visible to his no doubt horrified students, and then returning to the laboratory after class to record some more brain waves.

He was prolific, brilliant, and probably arrogant. His eldest son Paul once wandered through the halls of the Iowa Psychopathic Hospital looking for his father. A staff member asked him, “Who’s your father?” “My pop runs this place!” he replied. Of course, this wasn’t true, but he must have heard his father’s reports of all the research and other activity he engaged in there, and jumped to the conclusion that anybody that important must be in charge.

In the 1930s, Lee moved his wife, Pearl, and his three sons, Paul, Knight, and Duane, to California when he accepted a position at the University of Southern California. His movie-star physique, debonair mustache, and ready conceit were well suited to life in Lotusland. He had finally shucked off his dusty farm-boy ways and arrived in the big city, at the center of the entertainment world. He became an immensely popular instructor, especially in his large introductory course, which he despised teaching. Determined to cut down on enrollment, he adopted a strategy of being the most demanding, unforgiving, and distant professor on campus. It backfired, and his reputation as the toughest teacher caused the number of students in his classes to multiply.

He continued his research into stuttering and his measurements of brain activity, and published prolifically. As a tenured full professor, he had it made, academically speaking. But all was not well in his personal life. So focused was he on his scholarly ambitions that he neglected his wife and sons. Eventually, however, a lovely, thirty-ish redhead appeared in one of his classes. Divorced, with a teenaged daughter (my mother Patricia), she was an actress who was working on a Master’s degree in speech--the disciplines of speech pathology, speech communication, and drama being housed in the same department at the time. He was smitten, as was she. He was apparently determined that being in love was not going to cause his standards to fall, and so he gave her the only grade of “C” she ever received. She did not deserve it, and was livid. She agreed to marry him anyway.

In the 1940s, divorces were still scandalous. In fact, a divorce was grounds for dismissal from teaching at the university. Lee’s bride-to-be, who went by the name of Lysa, was then working as the Dean of Women. She and Lee met with the dean of the college about their problem. They loved one another, and wanted to marry. Lee would be divorcing his wife Pearl in order to marry Lysa. But he wished to continue as Professor and Chair of the Department of Speech. The dean agreed to bend the rules and allow Lee to retain his position, as long as neither he nor Lysa mentioned anything about their being previously married.

While Lee and Lysa were courting, Lysa’s daughter Pat, who was herself attending USC, had met in one of her classes a young man whom she soon began dating and eventually planned to marry. His name was Clayton Bennett, and he had studied opera briefly at one of the University of Nebraska campuses before heading to the West Coast to try a career in singing. After serving in the Navy, he used his G.I. Bill to enroll at USC, thinking he might use the knowledge of Russian and Italian he already had from his operatic studies as the basis for a foreign language teaching degree. Pat’s soon-to-be stepfather had other plans, however. He took Clayton aside, and suggested that a teaching career would not be the best way for his future son-in-law to support a young woman. He gave him an “have-I -got-a-deal-for-you” synopsis of the discipline of speech pathology, doubtlessly pointing out how Clayton’s interest in voice and in languages would be quite well served in the profession. Clayton got the message, and eventually earned his Ph.D. in speech pathology, with Lee Edward Travis as his dissertation director.

My father Clayton was one of so many men, and a few women, who had either studied under Lee or worked with him collegially. Some of his students were stutterers who gravitated to Lee to see if he might help them with their fluency, and many became his research subjects; eventually, many also stayed on to write dissertations under his guidance. Directly or indirectly, Lee Travis influenced much of an entire generation of speech pathologists earning their degrees in the 1940s and 1950s. Most had to read his Handbook of Speech Pathology. In the 1970s and 1980s, many more used the Handbook of Speech Pathology and Audiology as their bible, a gigantic tome containing contributions by a number of former Travis students who had cut their teeth on the first edition. After Lee moved to Fuller Theological Seminary to become the first dean of the School of Psychology, dozens of newly minted clinical psychologists in the 1970s and 1980s could also claim him as their academic father.

Some might have found it mysterious that Lee Travis wound up his multi-varied career at a theological seminary, but those who knew his story saw that this was not a departure, but a culmination, the closing of a circle. He was not just a member, but a Fellow of the American Psychological Association, with a license for clinical practice. He had continued the practice of psychology since receiving his doctorate at Iowa. At the Psychopathic Hospital there, one of his duties had been to conduct psychotherapy with his patients. Psychotherapy was a key part of his work with stutterers, even as he searched for a neurological cause. In World War II he was stationed at an airbase in Yuma, where he provided counseling for military personnel. (It was there, in the 100-plus degree heat of the desert, that he developed his habit of afternoon naps.) Even through the years at USC, he had always done some counseling, and for a while, he was a full-time therapist.

In 1957, Lee had left his position at USC to become a full-time psychotherapist in private practice on Beverly Hills’ Bedford Drive, sometimes referred to as “Couch Alley” for its preponderance of shrinks mental health professionals. He counseled the troubled and distraught among the rich and the famous. His clients included Anthony Quinn, who had sought help with his grief after one of his children drowned in a swimming pool at home; Richard Maibaum, a screenwriter best known for the James Bond films; the heir to the Otis Elevator Company fortune; and the President of Gibraltar Savings and Loan, whose son had been kidnapped and held for ransom in what was at the time a well-publicized case. In addition to rather exorbitant sums of money, Lee was rewarded with perquisites of various sorts. He served on the Board of Directors of Gibraltar Savings and Loan, and received shares of the corporation. He appears (though in disguise) in Anthony Quinn’s autobiography. But he also was rewarded with lasting friendships. I remember on numerous occasions sitting in Lee and Lysa’s big and elegant living room having cocktails and hors d’oeuvres with the Maibaums; I still correspond with Richard’s widow; one of the Maibaum’s sons became a psychotherapist himself. And as a teenager, I thought it was way beyond cool to look in my grandmother’s little book and see Anthony Quinn’s address and phone number in Rome.

Lee was like a movie star himself during the years of his Beverly Hills practice. He wore custom-made suits from Jack Taylor of Beverly Hills, perfectly fitted, often of silk or finely woven wool. He drove Cadillacs and Lincoln Continentals: the latter so attracted Anthony Quinn’s eye that he went out and bought one for himself. He traveled first-class to Europe, Asia, Britain, in many cases delivering papers at conferences or being the keynote speaker. He and my grandmother might lunch at the Brown Derby, where she would meet him after shopping at Saks Fifth Avenue and I. Magnin. They had a gardener, a maid, and a man who cleaned the pool. Dinner parties were cooked, served, and cleaned up after by a black woman wearing what looked like a French housemaid’s uniform: black dress and starched white apron. Throughout the meal, Lysa would ring a little bell, and Marie would scurry out with her assistant to clear the plates and bring the next course. As a rebellious, left wing revolutionary college student, I was mortified, of course. Their life was charmed, but it was materialistic and in many ways superficial. It was not the sort of life, one would suspect, of which Lee’s father would have been proud. And it did not last.

While Lee was determined to be an atheist, my grandmother Lysa was a died-in-the-wool Presbyterian whose grandfather had established the first Presbyterian church in Oklahoma’s Cherokee Strip in the nineteenth century. When she saw that a new church was being built off Mulholland Drive on the hill above their home, she insisted on attending. Lee did not wish to accompany her. She begged. He sneered that it was a “monument to superstition.” Perhaps it was the matter of that “C” grade at USC, for which Lee had not shown sufficient remorse. But for whatever reason, he relented, and agreed to go along with her the following Sunday to Bel Air Presbyterian Church. It was sometime in the early 60s.

What happened that day is documented in Lee’s autobiography, Ensnared in Love. He was overcome by powerful and inexplicable emotions. He was near tears, and felt as if he were shaking. He looked around to see if anyone was noticing the ordeal, but it was an inner turmoil with few visible signs. His experience was confounding; it was not rational. He showed no measurable effects, and yet he was profoundly moved. He realized that his spiritual nature, which he had so determinedly chosen to disbelieve, was rising up inside him in rebellion against his empiricism. Suddenly, God had reclaimed him.

Following this event, Lee went back to church with Lysa the next Sunday, and each Sunday after that. He bought a Bible, and read it from cover to cover, studying it as he would articles in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. And his personality changed dramatically. In place of his arrogance, humility appeared. Once unforgiving, he now forgave everyone. He knew his vocation was to serve, rather than to be served. And he opened his heart and his home to a new group of friends, fellow Christians whom formerly he might have secretly ridiculed.

Every week, young married couples came to Lee and Lysa’s house for prayer and fellowship and counseling. Theirs was a marriage very unlike those of other adult couples I knew in the 1960s. When they married, Lysa abandoned her career—at Lee’s request-- and her husband became her full-time job. She kept the books for his private practice, fixed his meals, made the beds, and served his cocktails. She was a most unconventional woman who became utterly traditional in her marriage. One might even say she lost herself in Lee, and she basked vicariously in the respect, renown, and lavish attention that people paid to Lee. She often literally sat at his feet; other times, they would sit together in a big lounge chair, squeezed in between the arms. They called each other pet names—she referred to him as “Man,” and he would call her “Woman” or “Baby.” These names would be written on gift tags under the Christmas tree: To Woman from Man. As an actress, she had found her starring role.

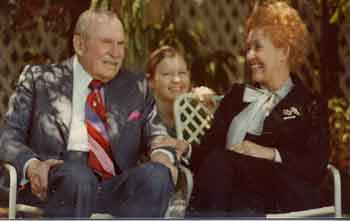

Lee had a pet name for me as well, “My Little One.” I was not the youngest grandchild, and indeed, technically, I was his step-grandchild, but Lee was much closer to my two brothers and me than he was to any of his blood-related grandchildren. He was the only grandfather I knew. When I married, he called my husband “Profundo.” My husband would call Lee “Basso.” They would periodically stand with their arms over one another’s shoulders and exchange these names several times: “Well, Basso?” “Well, Profundo?” “Basso?” “Profundo?”

Lee changed in other ways. He began to write poetry for the first time in his life, and as I was doing the same, we often shared our work. As I struggled to make my poetry into art, I often came up with something convoluted and obscure. But Lee’s poems were very straightforward, which is not to say simple. They might harken back to his days on the wind-swept plains, what he called his childhood “Prairie Dog Town.” Other pieces focused on his love for Lysa, and some were prayers. When he had a few poems published in Acta Symbolica, he seemed as proud of these as any of his scholarly works.

His final career move was also the result of the conversion experience. When Fuller Theological Seminary decided to open a School of Psychology to train clinicians who could integrate the practice of psychology with Christian faith, the administrators needed someone to be the founding dean. Because this person would shape the school and be responsible for getting accreditation from the American Psychological Association, he or she had to be a person with impeccable credentials, a proven and influential scholar. But the person also had to be a Christian, and Christians were notoriously hard to find among the most distinguished scholars in psychology. Lee clearly was a likely candidate, and he was approached for the job. He was of course humbled and honored, as well as interested, but there was one hitch: the salary would be shamefully low.

After Lee and Lysa discussed it, however, Lee felt strongly that he was being called to serve out the rest of his days at Fuller. He abandoned his lucrative practice in Beverly Hills, though not his practice at home, to become the first Dean of the School of Psychology at Fuller. He preached what he believed, and he practiced what he preached. Since Fuller was a Christian school, instead of offering written contracts, all appointments were made orally and sealed with a handshake. He would trust his faculty to do their jobs, and they would trust him to support them. In the classroom, Lee no longer acted the cold and uncompromising part. He assured his students at the beginning of every term that they began with an A grade, and they would finish with an A unless they worked very hard to lose it. Once, I was agonizing for hours over whether to change a student’s grade from a B+ to an A, to boost his chances of getting into medical school. “Give him the A,” was my grandfather’s advice, uttered in passing, as if it were the simplest decision in the world.

And that is the way Lee treated everyone in his latter years. He had utter faith in God and in His creatures. He forgave people when they could not forgive themselves, and he loved people even when they felt unlovable—in fact, he was the only person I ever knew who genuinely practiced unconditional love. He was a man full of joy, who laughed as easily and simply as a Nebraska farm boy. I can still hear his honey-toned baritone voice singing “The Streets of Laredo.” And I can still see him looking at me with a twinkle that told me he saw me for who I really was, underneath my bad moods and my stupid mistakes, my inconsiderate remarks and my failure to live up to his expectations. He saw me, and loved me anyway.