Unit 3: Do the Interests of Others Matter?

Photo: Colleen Hayes / NBC.

In Unit 3 of the course we move into Normative Ethics by considering to what extent (if any) we ought to consider the interests of others. Some of you might immediately feel this question is a non-starter: it is simply human nature for a person to only care about promoting their own interests without a real concern for anyone else. This is a bold claim of Psychological Egoism, the subject of this module.

In our exploration of Psychological Egoism, we have 3 learning outcomes. By the end of this module, you will be able to…

- Explain the meaning of Psychological Egoism,

- Assess some arguments in favor of Psychological Egoism, and

- Summarize the fundamental challenges underlying stronger forms of Psychological Egoism.

Read & Annotate This:

|

Psychological Egoism

|

Context

As I will use it for this course, prudence refers to a general responsiveness to one’s own interests. So if I am solely interested in physical pleasure, it is prudent for me to do things that give me physical pleasure, while it is imprudent for me to avoid opportunities for such pleasure. Of course, you may be solely interested in intellectual accomplishment, so it is prudent for you to do things that lead to intellectual accomplishment, while it is imprudent for you to avoid seeking out such accomplishment. Meanwhile, another person may be solely interested in the happiness of their family, and so it is prudent for them to make their family happy, and so on.

In contrast with prudence, I will define altruism as a general responsiveness to the interests of others, even when doing so may require the sacrifice of one’s own interests. So if it meant helping others, an altruist is willing to give up their own physical pleasure, their own intellectual accomplishment, the happiness of their family, or whatever else it is that altruist values.

Putting this together, we may define Psychological Egoism as a theory of human motivation claiming that a person primarily acts according to prudence. This theory can come in strong or weak forms:

- Strong Psychological Egoism claims a person will always act prudentially, making altruism impossible or abnormal.

- Weak Psychological Egoism claims a person will often act prudentially, though altruism does occasionally occur and is normal.

Notice Psychological Egoism is a descriptive theory about human behavior. It tells us how people tend to behave, but not how they should behave.

The reading from James Rachels (2003), however, casts doubt on strong versions of this theory by revealing several difficulties that emerge from it.

Strong theories of Psychological Egoism have a long history, going back (at least) to the ancient Greeks. So I have included (in the optional “Curious for More?” section below) an excerpt from Plato’s Republic (ca. 380 B.C.E./2004). Here the character Glaucon tells Socrates the story of a ring that can turn its wearer invisible (like the One Ring from The Lord of the Rings). The shepherd Gyges of Lydia finds the ring and uses it to do all sorts of horrible things.

This story raises the interesting question: what would a moral and ethical person do with such a ring? Glaucon suggests that even a good person would also do horrible things because that person could get away with them. Glaucon is therefore defending a very strong theory of Psychological Egoism, coupled with the rather cynical belief that the interests of people tend to be particularly selfish and potentially destructive to others.

Finally, just for fun, I have also included (again, in the optional “Curious for More?” section below) a nice little discussion of Psychological Egoism that the Philosopher Todd May put together for the TV show, The Good Place, which aired a few years ago.

Reading Questions

As you read, keep these questions in mind:

- Based on how I have defined it, what do you think it actually means for you to be prudent? Is prudence about doing what makes you happy? Or is prudence about preserving your own life? Are these different or do they amount to the same thing? Or is prudence about something completely different from concerns with happiness or self-preservation?

- According to James Rachels, how might Psychological Egoism interpret Raoul Wallenberg’s actions?

- What are the two arguments for Psychological Egoism presented by Rachels? How does Rachels criticize each of them?

- What does Rachels claim to be the “deepest error” (2003, p. 72) with Psychological Egoism?

Although I strongly suggest that you write out brief answers to these questions, you do not have to turn in written responses. You do, however, need to be prepared to answer questions like these on module quizzes and the unit exams.

References

The Good Place. (2018, December 28). Mother Forkin’ Morals with Dr. Todd May - Part 3: Psychological Egoism - The Good Place (Exclusive) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wtpIsRk8tzg

Plato. (2004). [The ring of Gyges]. In C. D. Reeve (Trans.), Republic (pp. 37–39). Hackett. (Original work from ca. 380 B.C.E.)

Rachels, J. (2003). Psychological egoism. In The elements of moral philosophy (4th ed., pp. 63–75). McGraw-Hill.

Watch This:

|

Video 1

|

Video 2

|

|

Video 3

|

Video 4

|

|

Video 5

|

Video 6

|

|

Video 7

|

Video 8

|

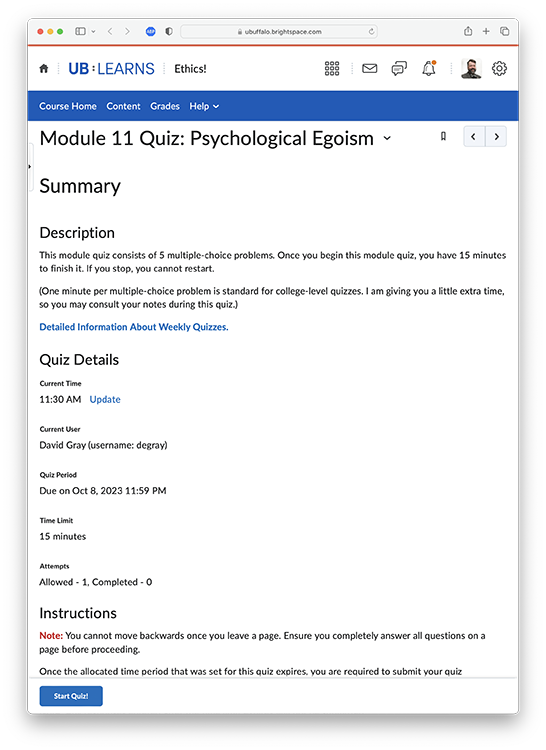

Do This:

|

Module 11 Quiz

Due: October 7 |

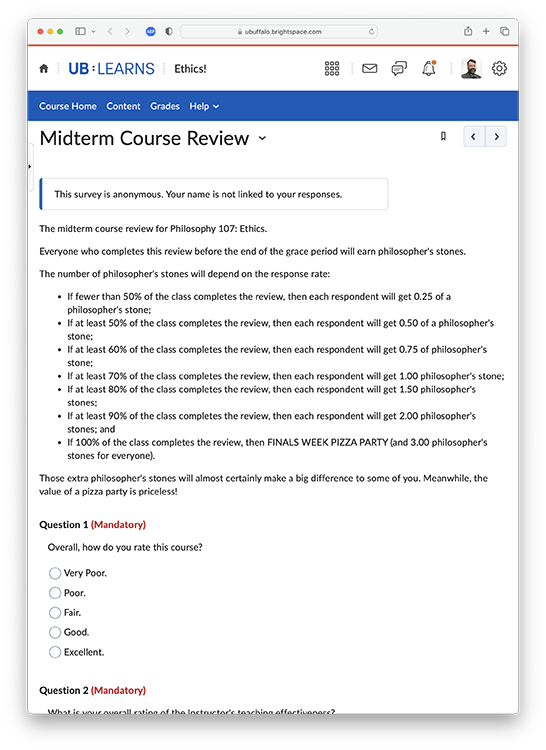

Midterm Course Review

Due: October 7 |

Curious for More? (Optional)

|

The Ring of Gyges

|

Todd May explains Psychological Egoism with some references from The Good Place.