![]()

![]()

Continental Philosophy

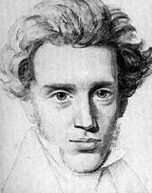

Kierkegaard – Subjectivity

Primary Source:

- Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript, “The Task of Becoming Subjective”, “Truth is Subjectivity”, and “The Subjective Thinker", in KA, pp. 207-231

Background:

From the Routledge Online Encyclopedia:

In an early entry in his journals, written when he was still a student, Kierkegaard gave vent to the dissatisfaction he felt at the prospect of a life purely devoted to the dispassionate pursuit of knowledge and understanding. “What good would it do me”, he then asked himself, “if truth stood before me, cold and naked, not caring whether I recognized her or not?” Implicit in this question was an outlook which was to receive mature articulation in much of his subsequent work, being particularly prominent in his criticisms of detached speculation of the kind attributable to those he called “systematists and objective philosophers”. To be sure, and notwithstanding what has sometimes been supposed, he had no wish to be understood as casting aspersions on the role played by impersonal or disinterested thinking in studies comprising scholarly research or the scientific investigation of nature: such an approach was quite in order when adopted within the limits set by determinate fields of enquiry. But matters were different when philosophical attempts were made to extend it in a manner that purported to transcend all particular viewpoints and interests, this conception of the philosopher’s task leading to the construction of metaphysical theories which sought to comprehend every aspect of human thought and experience within the disengaged perspective of objective contemplation. Kierkegaard considered Hegel to be the foremost contemporary representative of the latter ambition, the famous system to which it had given rise being in his opinion fundamentally misconceived.

[In reference to the readings on the Paradox of Faith,] Kierkegaard was certainly not alone in suggesting that writers who tried to justify religious belief on cognitive grounds were more confused about its true nature than some of their sceptically minded critics and to that extent posed a greater threat to it; indeed, Kant himself had virtually implied as much when he spoke of denying knowledge to make room for faith, as opposed to seeking to give religious convictions a theoretical foundation that could only prove illusory. The question arose, however, of what positive account should be given of such faith, and here Kierkegaard’s position set him apart from many thinkers who shared his negative attitude towards the feasibility of providing objective demonstrations. As he made amply clear, the religion that crucially concerned him was Christianity, and far from playing down the intellectual obstacles this ostensibly presented he went out of his way to stress the particular problems it raised. Both its official representatives and its academic apologists might have entertained the hope of making it rationally acceptable to a believer, but in doing so they showed themselves to be the victims of a fundamental misapprehension. From an objective point of view, neither knowledge nor even understanding was possible here, the proper path of the Christian follower lying in the direction, not of objectivity, but of its opposite. It was only by ‘becoming subjective’ that the import of Christianity could be grasped and meaningfully appropriated by the individual. Faith, Kierkegaard insisted, ‘inheres in subjectivity’; as such it was in essence a matter of single-minded resolve and inward dedication rather than of spectatorial or contemplative detachment, of passion rather than of reflection. That was not to say, though, that it amounted to a primitive or easy option. On the contrary, faith in the sense in question could only be achieved or realized in the course of a person’s life at great cost and with the utmost difficulty.

Kierkegaard’s stress on the gap separating faith from reason, which it could need divine assistance to surmount, was reflected in the controversial account he offered of religious truth; this likewise received a subjective interpretation. Thus in [these passages on subjectivity] he contrasted two distinct ways of conceiving of truth, one treating it as a matter of a belief’s corresponding to what it purported to be about and the other as essentially pertaining to the particular manner or spirit in which a belief was held. And it was to the second of these conceptions that he ostensibly referred when he declared that ‘subjectivity is the truth’, genuineness of feeling and depth of inner conviction being the decisive criterion from a religious point of view. Admittedly he has sometimes been criticized here for a tendency to shift from construing religious truth along the above lines to doing so in terms of the objective alternative, with the questionable implication that sheer intensity of subjective acceptance was sufficient to authenticate the independent reality of what was believed. But however that may be, it is arguable that in this context – as is often the case elsewhere – his prime concerns were conceptual and phenomenological in character, rather than epistemic or justificatory. Kierkegaard’s central aim was to assign Christianity to its proper sphere, freeing it from what he considered to be traditional misconceptions as well as from the falsifying metaphysical theories to which there had more recently been attempts to assimilate it. If that meant confronting what he himself called ‘a crucifixion of the understanding’, the only appropriate response from the standpoint in question lay in a passionate commitment to the necessarily paradoxical and mysterious content of the Christian religion, together with a complementary resolve to emulate in practice the paradigmatic life of its founder.

Questions:

- How does Kierkegaard distinguish between objective and subjective truth?

- What does he mean by “truth is subjectivity” and how does this relate to the idea that truth involves passion, commitment, and risk?

I love Apache! So should you!

![]()