Task Analysis

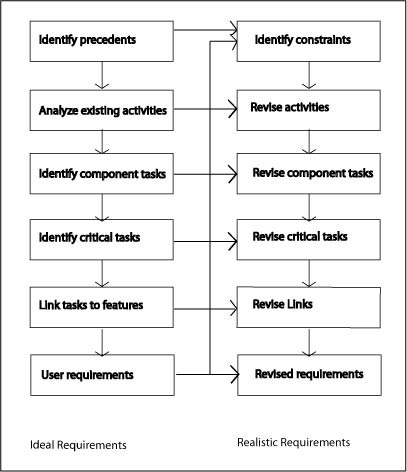

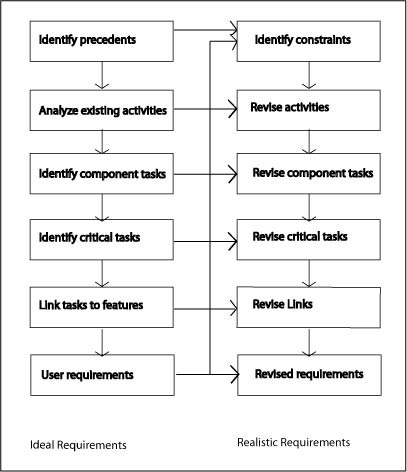

The diagram below describes the task analysis process.

Description of steps in Task Analysis:

Identify tasks. In this step, the designer determines the tasks that need to be supported. So, for example, the tasks of using a large public restroom may include:

Analyze existing tasks. Typically, but not always, designers have some existing environment (precedent) to inform the analysis. It may be an existing building owned by the client, a product currently produced by the client, a system that is considered a best practice in the field or simply a similar environment that the designer feels is a good model for the new project. This existing environment will be used to identify the component tasks that need to be accommodated. The designer may identify several different precedents rather than focus on just one. At this point, the designer should identify what features these environments contain and how do the precedents differ in that respect from one another.

Identify component tasks. Each one of the tasks identified abover has a set of component tasks. For example, defecation may include: entering a private stall, locking the door, installing sanitary seat protector, partially udressing, transferring to the seat, etc. It is also useful to determine how the tasks relate to one another and the different sequences in which they may be completed. The analysis can best be organized as a series of diagrams including illustrations of the tasks and component tasks can be useful. Note that after this part of the analysis is completed, it is likely that some revision of the original goals may be necessary. Information on component tasks may be availabe in the research literature. If available information is not adequate for the project, research may be needed including surveys, interviews, observations of actual use, and/or focus groups.

Identify critical tasks. Not all the tasks are as important as others. To simplify the analysis, it may be worthwhile focusing on critical tasks. At this point, some input from end users is definitely needed. They may have very different perspectives on the critical tasks than the designers. Moreover, there may be major differences between one user group and another. In the case of restrooms, for example, one could expect differences in perspectives between men and women, adults who use restrooms alone and those who do so with children in tow. Information on priorities may be availabe in the research literature but it is useful to conduct interviews and focus groups to validate previous research and make sure it is applicable to the specific design project.

Link to features. One the critical tasks are identified, the designer needs to link them to the features of the environment. What features are needed - that is, which parts of the environment support which tasks and sub-tasks? For example, finding the women's restroom would be linked to the entry shape, color and configuration and to signs and symbols that designate the intended users of the room. Again, a graphic presentation of these linkages would be useful.

User requirements. At this point, the designer determines what the desired relationships between tasks and features should be in terms of user requirements. Research, including study of precedents, can be used to determine the requirements but, when possible, it is valuable to validate designer-generated requirements with direct user interaction such as through focus groups, especially with critical tasks and in projects where the design will be mass produced. The validation process should always include flexibility to add new requirements during interaction with end users. Requirements can be documented in many ways along a continuum of general to specific. On one pole is the "performance requirement" in which the performance of the product is stated without specifying how it should be realized, e.g. a person should be able to enter a toilet stall with a luggage cart and close the door. On the other pole is the specification of features. What specific characteristics should the design have, e.g. how large should the toilet stall be and what configuration should it have to accommodate the performance requirement? In general, it is better to include both the performance goal and the specification of the features. There may be several optional specifications, e.g. if no-hands flushing is the performance requirement, it could be acheived with an automatic flush device activated by a motion sensor, a motion sensitive switch that the user must consciously activate or a switch mounted on the door that activates every second time the door opens.

Identify constraints. Once the ideal user requirements are determined, constraints need to be determined to insure that the final set of user requirements is realistic. Constraints may include outside influences like government regulations (e.g. building codes, consumer safety standards, etc.). They may also include other project goals like sustainability. They may also include ergonomic issues related to the specific targeted user groups, e.g. cultural issues, age differences, etc. Finally, they include feasibility concerns like cost, availability of products, and reliability of available technology.

Once constraints are identified, each of the steps needs to be revisited to consider their implications. The end result is a set of realistic user requirements.

[Home] [Description] [Schedule] [Readings] [Notes] [Assignments] [Teams]